In the year 1 B.P. (1 Before Pandemic, or 2019 in other words) I was in Buenos Aires and a visit to El Ateneo, a spectacular bookstore there reminded me of Jorge Luis Borges’ quote, “I had always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library“.

Over the last year or more, I have been visiting libraries in many cities – ostensibly for archival work, but truth be told, mainly to grab slices of paradise on earth. As Amir Khusrau might well have said, “Firdaus bar roo-e zameen ast: hameen ast-o hameen ast-o hameen ast.”

Over the last year or more, I have been visiting libraries in many cities – ostensibly for archival work, but truth be told, mainly to grab slices of paradise on earth. As Amir Khusrau might well have said, “Firdaus bar roo-e zameen ast: hameen ast-o hameen ast-o hameen ast.”

The reading room of the Widener library at Harvard (on the left) is one such, a source of equal parts bliss and solace. The peace that emanates draws large numbers of readers – and has done ever since it was built in 1915 as a memorial to Harry Elkins Widener’07 by his mother. Poignantly, she and her maid survived the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912, while he, his father, and his valet drowned. Built in a period of less than three years, this monumental library is the fulcrum of the university, and one of its early denizens was DD Kosambi (the subject of many a post on this blog, and one of the reasons for me to visit there in the recent past) who mentioned it often and in various contexts. Preparing for an exam as a sophomore, on the 22nd January 1927, DDK asks, “Why is it that a paper that can be completely solved within thirty minutes in the Widener reading room takes all of three hours in an examination hall?” Further evidence of the magical properties of libraries!

I spend a little more time at the Pusey and Houghton libraries – these are right next to the Widener, but they contain much of the archives I need to consult: letters, diaries, documents from a century or more ago. And learning how to use them is an education in of itself, the discipline goes well beyond speaking in hushed tones. Not being able to carry in any pen or paper, for instance, and not handling more than one document at a time, resting valuable books in foam wedges (the image above is from some commercial site) so as to preserve the binding… One has to learn to be careful, and also to be caring of this valuable heritage. Which, clearly, much of it is. The Pusey, named for an earlier President of Harvard, contains all the papers of the University, while the Houghton, which was built in the 1940’s, houses rare books and manuscripts.

I spend a little more time at the Pusey and Houghton libraries – these are right next to the Widener, but they contain much of the archives I need to consult: letters, diaries, documents from a century or more ago. And learning how to use them is an education in of itself, the discipline goes well beyond speaking in hushed tones. Not being able to carry in any pen or paper, for instance, and not handling more than one document at a time, resting valuable books in foam wedges (the image above is from some commercial site) so as to preserve the binding… One has to learn to be careful, and also to be caring of this valuable heritage. Which, clearly, much of it is. The Pusey, named for an earlier President of Harvard, contains all the papers of the University, while the Houghton, which was built in the 1940’s, houses rare books and manuscripts.

The trouble with ferreting around in archives is that one file leads to another, and to another, and before one knows it, one is down some deep rabbit holes… Which is one reason that last month I landed up at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, looking at some correspondence between Kosambi and Robert Oppenheimer.

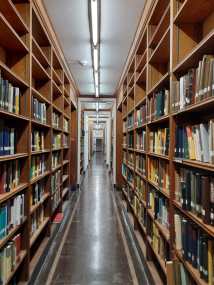

The library of the IAS is not very large, being so much more specialised than a University library. As it turns out, Oppenheimer’s papers are in the Firestone Library at Princeton University next door, but at some offsite location so I couldn’t get to see them. The archives at the IAS are a treat as well, leading to a day well spent in these environs. Many of the Indian visitors to the IAS in the early years (1940’s and ’50’s) were somehow connected with the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research – Bhabha, Kosambi, Chandrasekharan – and this was a time when the physical library was seen as crucial to building up any academic institution. Ironically, the realisation that with the passage of time, the volume (and weight) of journals and books in a growing library would become too large to be sustained — leading to the digitization of all journals, beginning with JSTOR — would start at Princeton. Mercifully, while digitial libraries have largely addressed the issue of access to scholarship, they have not obviated the need for the physical library for those that need the space to feel and smell paper books.

The library of the IAS is not very large, being so much more specialised than a University library. As it turns out, Oppenheimer’s papers are in the Firestone Library at Princeton University next door, but at some offsite location so I couldn’t get to see them. The archives at the IAS are a treat as well, leading to a day well spent in these environs. Many of the Indian visitors to the IAS in the early years (1940’s and ’50’s) were somehow connected with the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research – Bhabha, Kosambi, Chandrasekharan – and this was a time when the physical library was seen as crucial to building up any academic institution. Ironically, the realisation that with the passage of time, the volume (and weight) of journals and books in a growing library would become too large to be sustained — leading to the digitization of all journals, beginning with JSTOR — would start at Princeton. Mercifully, while digitial libraries have largely addressed the issue of access to scholarship, they have not obviated the need for the physical library for those that need the space to feel and smell paper books.

The TIFR library, in 1981 when I first went there, was pretty much as good as any other library in the world in terms of what it contained in physics and mathematics. What was an endearing feature of the mathematics books at least was the purely alphabetical mode of shelving – none of the Ranganathan colon classification or the Dewey decimals that plagued most other libraries. One found Weil close to Weyl (if not next to each other) and Hardy and Hilbert not too far from each other as well, so the chances of serendipity were very real, leading to another set of days well spent or happily wasted, depending on how one looks at it.

The TIFR library, in 1981 when I first went there, was pretty much as good as any other library in the world in terms of what it contained in physics and mathematics. What was an endearing feature of the mathematics books at least was the purely alphabetical mode of shelving – none of the Ranganathan colon classification or the Dewey decimals that plagued most other libraries. One found Weil close to Weyl (if not next to each other) and Hardy and Hilbert not too far from each other as well, so the chances of serendipity were very real, leading to another set of days well spent or happily wasted, depending on how one looks at it.

The most difficult part of my moving to JNU was having to give up the TIFR library: this was before the internet or email was widely accessible, so also well before PCs and scanners were ubiquitous, and well before the digitization of journals was a twinkle in anybody’s eye. In 1986, the JNU library system was to put it mildly, in shambles. The new library building had been constructed (a visibly leaning tower, I think) but the fire-safety issues had not been sorted out for one thing, so moving the existing collection there was going to take time. The architecture was not, again to put it mildly, book friendly, especially given Delhi weather, the heat and the dust. To add to which, there were no books in physics or mathematics given that the School of Physical Sciences was just starting then. I had to go to the Indian Statistical Institute down the road from time to time, and to the Delhi University library at least once a month, graduate students in tow, to see what the latest issues of Physical Review Letters might contain. I don’t remember the discomfort or the irritation – those were happy times in their own way. Now renamed the B R Ambedkar Central Library, the JNU Library is visibly struggling – the collection is not growing, the premises are poorly maintained, the staffing is inadequate – sure ways to kill the lifeline of a university. Still, imperfect as it is, it serves a purpose – for many this is a site of imagined opportunities.

The most difficult part of my moving to JNU was having to give up the TIFR library: this was before the internet or email was widely accessible, so also well before PCs and scanners were ubiquitous, and well before the digitization of journals was a twinkle in anybody’s eye. In 1986, the JNU library system was to put it mildly, in shambles. The new library building had been constructed (a visibly leaning tower, I think) but the fire-safety issues had not been sorted out for one thing, so moving the existing collection there was going to take time. The architecture was not, again to put it mildly, book friendly, especially given Delhi weather, the heat and the dust. To add to which, there were no books in physics or mathematics given that the School of Physical Sciences was just starting then. I had to go to the Indian Statistical Institute down the road from time to time, and to the Delhi University library at least once a month, graduate students in tow, to see what the latest issues of Physical Review Letters might contain. I don’t remember the discomfort or the irritation – those were happy times in their own way. Now renamed the B R Ambedkar Central Library, the JNU Library is visibly struggling – the collection is not growing, the premises are poorly maintained, the staffing is inadequate – sure ways to kill the lifeline of a university. Still, imperfect as it is, it serves a purpose – for many this is a site of imagined opportunities.

For the past year I have been ensconced in the Prime Ministers Museum & Library, earlier the NMML (NM for Nehru Memorial) several times a week. Their archives of modern India are superb in terms of depth and breadth of content and while the delivery is not quite at the level that libraries in the US are able to provide, it is not far behind. I can carry in pens and books, and cannot take any photographs, for instance, and all requests for photocopies need to be done on paper (mercifully not in triplicate) but it all works well enough. This is a national resource of inestimable value and we do need to give it the funding it requires with few questions asked.

For the past year I have been ensconced in the Prime Ministers Museum & Library, earlier the NMML (NM for Nehru Memorial) several times a week. Their archives of modern India are superb in terms of depth and breadth of content and while the delivery is not quite at the level that libraries in the US are able to provide, it is not far behind. I can carry in pens and books, and cannot take any photographs, for instance, and all requests for photocopies need to be done on paper (mercifully not in triplicate) but it all works well enough. This is a national resource of inestimable value and we do need to give it the funding it requires with few questions asked.

And in all this, I have become deeply aware of the cognitive generosity of librarians. Many members of this tribe take it as a given, that they have a social responsibility to enable those that come into a library, to find what they seek or more often, to find what they need to seek, even if they do not immediately know what they are looking for. So often I have found that an archivist or librarian I have approached has ordered resources for me, sometimes gone out of their way to search for the things I needed, without themselves being interested in the questions that drove me there. Philosophers and psychologists do point out that we all have a cognitive generosity through which we all share information about ourselves, but this is a little different – for most librarians, the nature of the question is in of itself not very important; what is more important is that they will do a lot to help you find the answer, even if it means stretching their own resources and without being even remotely interested in whatever the topic is. I have seen this happen at the Widener, at Firestone, at PMML, at JNU and at other libraries across the world, and have been struck by how genuine this generosity is.

I could go on reminiscing about the different libraries that I have been fortunate enough to spend time in, their architecture, their holdings, and the librarians who have helped me, but that will have to wait for another day. At this time the role and nature of libraries is changing, and it serves us well to remember that the context of the Borges quote, while evoking the imagery of a bibliophile’s Xanadu, is in fact bittersweet. In 1955, when his vision was failing, he was made the Director of the National Library of Argentina, prompting him to say

“Little by little I came to realize the strange irony of events. I had always imagined Paradise as a kind of library. Others think of a garden or of a palace. There I was, the center, in a way, of nine hundred thousand books in various languages, but I could barely make out the title pages and the spines. I wrote the Poem of the Gifts which begins:

No one should read self pity or reproach

Into this statement of the majesty

Of God; who with such splendid irony

Granted me books and blindness at one touch.”

Today all of us carry devices – our smartphones – that put us all in the centre of millions of books in various languages, but the screens are small, needing some effort to see the titles, and more effort to read them, so the splendid irony persists.

Perhaps we need haptic devices that will remind us more accurately of why mankind invented the physical book, why we need libraries to go to, and why we revere Gutenberg. One of the bibles that he printed is there in the Elkins Room at the Widener, and during each visit I do go by to see it and to remind myself that this is, in my own imagination too, paradise.

Ah, libraries! And in Princeton!!

LikeLike

One day only, but so good to be there!

LikeLike

I think I probably told you I was a Summer Visitor this year for May, June and July. I love those libraries – even if the Firestone no longer houses all its books on open access.

LikeLike