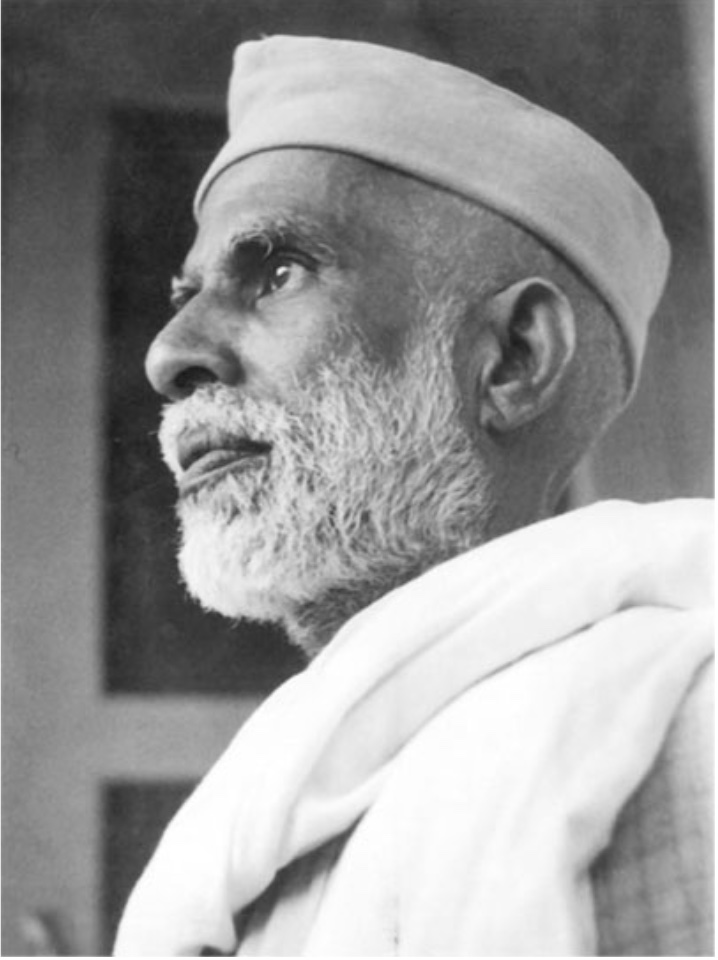

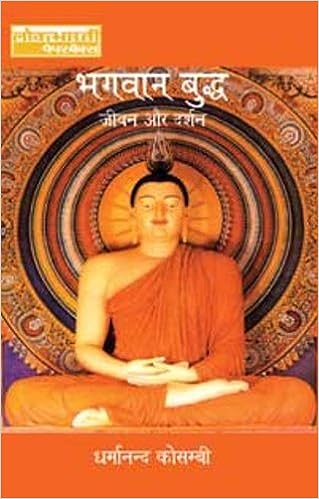

Dharmanand Kosambi died in a manner of his choosing, and almost at a time of his choosing. By mid 1946 he had tired of life: his diabetes was causing him acute physical discomfort, Indian independence – for which he had worked hard alongside Gandhiji in the preceding years – was a certainty, his book on the Buddha was widely read and widely appreciated, and he felt that there was little else that he could contribute.

“When Kosambiji realized that he was no longer physically fit to carry on any work, he decided to give up his life through fasting. ” Speaking at the prayer meeting on 5 June, Mahatma Gandhi recalled the manner in which his close associate Dharmanand elected to die. Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain traditions all endorse, under special circumstances, ritual starvation that leads to death. Even today, there are recorded instances of Jain monks undertaking Sallekhana each year, which is the most formalised of the fasting traditions, to be undertaken when one is afflicted by an incurable disease, under circumstances when one fears the loss of character or dignity, old age and impending death, or when the body and senses get weak.

Dharmanand had already begun a fast in 1946, but Gandhiji (advised by Purushottam Das Tandon) intervened. “Bapuji asked me to give up my fast, and in deference to his wishes I did so. I had no painful symptoms then, nor even this itch which I now have, and I could have then died in peace. But out of his love for me Bapuji wired to me again and again to desist from fasting. I gave it up at his request on the 23rd of September and have undergone much physical suffering ever since. Ultimately, I had to resort to fasting once again. Bapu is not to blame for all that has happened because he did it from the best of motives. Nor am I sorry for all the agony which I have had to suffer for, as the Lord Buddha has said, ‘Forgiveness in the form of titiksha (endurance), is the greatest austerity.’”

Dharmanand came to Sevagram in 1947 and Balvantsinha, a follower of Mahatma Gandhi who lived in the Ashram described the times in “Under the Shelter of Bapu” that was published in 1962. Writing on the 12th of May, 1947, he says about Dharmanand, “His health had seriously deteriorated. He could not digest anything. He had asked for Bapuji’s permission to live merely on water and thus eventually to shed his useless body. As for obsequies, he wished that the disposal of his dead body should be done in the cheapest possible manner and suggested that burial would be the best under the circumstances.”

Insofar as this decision was religious, it was Buddhism that motivated Dharmanand, who wanted to pass on Buddha Purnima, 5 May 1947. Nevertheless, the lack of solid food or Bhakta Pratyakhyan, the decision to stay in one place or Inginimaran, and keeping away his children and refusing the concern of others, Paadpogaman, all were aspects of the Jain tradition of Sallekhana.

There is a strange contemporaneity to this mode of dying. In countries where the so-called accompanied suicide is permitted today, there is considerable similarity to the formal requirements: the person has to be of sound judgement, should be suffering from a disease which will lead to death (terminal illness), and/or an unendurable incapacitating disability, and/or unbearable and uncontrollable pain. (Because this form of death requires the ingestion of a drug, there is the further requirement that the person should possess a minimum level of physical mobility, sufficient to self-administer the drug.)

But surely Gandhiji would have felt a tinge of regret later when he noted that due to the first fast in 1946, Dharmanand’s “digestion had been severely affected and he was not able to eat anything at all. So, in Sevagram, he again gave up food.” Writing to Balvantsinha, he gives the instruction, that “Kosambiji may live on water, if he cannot digest any food whatever. If he cannot take even water, then, of course, there is no help and the body will slowly die. Inner peace being established, there remains nothing more to be achieved.”

For a month, Dharmanand lived on, an inspiration to others in the Ashram. Deeply concerned about the further propagation of Pali and Buddhism, he wanted reassurance that Gandhiji would endorse his plans for sending students to Sri Lanka. Gandhiji was not so sure that this would be useful. At any rate, it was clear to Balvantsinha, Vinoba Bhave, and others that they were in the company of an exceptional person. “In the eleven years of the Ashram’s history, Kosambiji’s death was the first to occur. I have never seen a nobler and a more serene death in my life,” says Balvantsinha.

Dharmanand passed at 2:30 pm on 4 June, with Balvantsinha in attendance. “At about 12 noon, he said that he was now about to depart. At 2 p.m., he drank a little water and asked me to open all the doors, as though someone had come to carry him away and the doors had to be kept open for them to pass out. He had never before requested me to keep the doors open. The throb of life in his body gradually slackened and he expired exactly at 2:30. Between the moment till which he continued to speak in full consciousness and the time he drew his last breath, there was not more than ten minutes’ interval.”

Dharmanand passed at 2:30 pm on 4 June, with Balvantsinha in attendance. “At about 12 noon, he said that he was now about to depart. At 2 p.m., he drank a little water and asked me to open all the doors, as though someone had come to carry him away and the doors had to be kept open for them to pass out. He had never before requested me to keep the doors open. The throb of life in his body gradually slackened and he expired exactly at 2:30. Between the moment till which he continued to speak in full consciousness and the time he drew his last breath, there was not more than ten minutes’ interval.”

The decision to keep both his son Damodar and his daughter Manik away in the last month was more than a little harsh. There was a special closeness among the three, especially in the years 1918 – 1928, when they traveled to America and lived in Cambridge, MA, with Manik at Radcliffe, Damodar at the Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, and then at Harvard, and Dharmanand at Harvard. Although not given to overt displays of affection, and while they were used to long periods apart from each other, the mode of their father’s death left both of them and their families quite shaken, even though they all knew of his intentions and had said their goodbyes.

Dharmanand had left it to Gandhi to decide what to do with his effects, and had apparently wished that his body be buried since it would be cheaper. Gandhiji, though, felt that cremation would be more appropriate, and within a few hours this was carried out, in the presence of Kakasaheb Kalelkar and Vinoba Bhave. (Thirty-five years later, Vinoba Bhave would choose to die in the same way, refusing food and medicine.)

Dharmanand Kosambi’s death, as noble as his life had been, Balwantsinha records, was an inspiring sight of solemn splendour. Those were times when sacrifice, simplicity, and austerity were greatly admired and emulated. At a prayer meeting the next day, Gandhiji was overcome with emotion and devoted the first part of his address to an appreciation of the life and work of Kosambi.

“I have no doubt whatsoever that his stay in the Ashram has sanctified it.”