Round the corner from the improbably named Chaos Control Cafe in Parel (“Where Chaos is under control with harmony”) is the Bahujan Vihāra that was built between 1935 and 1937. I had gone in search of the Vihāra (finding the CCC was sheer serendipity!) based on what I had read in Meera Kosambi’s account of her grandfather’s life, as well as what another granddaughter of his, Mrs Indrayani Sawkar (neé Kunda Sathe) wrote in a fictionalized biography of Dharmanand, Man from the Sun. In Dharmanand Kosambi: The Essential Writings, Meera Kosambi has this to say:

“A concrete form of Dharmanand’s effort to spread the knowledge of Buddhism was a long-cherished task of building a Buddhist vihara in the mill area of Parel in Mumbai. It was named ‘Bahujan Vihara’ — rather than Buddha Vihara — because of its focus on mill workers and Dharmanand’s experiment to eradicate caste discrimination and untouchability among them. He enlisted the help of the philanthropist Shet Jugal Kishore Birla, who had already built Buddhist temples and rest-houses at places such as Sarnath, Kushinara, Calcutta, and Darjeeling. The building was completed in 1936 and the plaque near the entrance mentioned Birla’s donations and other contributions; Dharmanand’s name is nowhere to be found. He stayed here until the end of 1939, working in various ways: he gave discourses every Sunday, and taught Pali and Buddhism — taking pride in the fact that he taught Pali to a Dalit student (of Mahar descent) who had passed his BA in Sanskrit and was now studying for his MA.”

Sawkar is more florid. Writing in Man from the Sun about her grandfather, who was also known as Bapu, she says that in 1935 he “took up residence at Mumbai and began to build his Bahujana Vihara, a vihara for the workers, the mill workers mainly. Jugalkishor Birla had sponsored the project on the condition that Bapu himself supervise the work. The project represented a culmination of Bapu’s devotion to Buddhism and his interest in improving the plight of the masses. The site chosen was in the quarter of the mill-workers popularly known as Girangaon, the cotton mill city, a very crowded part of Mumbai. The vihara would furnish the workers with a nice, quiet place for discussions and get togethers. That is why he had named it Bahujana Vihara. It was socialism in an old style Buddhist temple. The vihara got completed in a year. It is still there. A plaque embedded in its wall informs the visitors that Jugalkishor Birla gave 19,000 rupees for its construction […] Bapu’s name is nowhere there, by his own insistence. Bapu was immensely attached to his Bahujana Vihara. He had a small cell here wherein he read, wrote and meditated. […] He taught whomsoever wished to learn Pali. He found many students amidst the Nav-Bauddhas. On Sundays he gave sermons about a Buddhist or socialistic topic, equality, education, unions and freedom. Workers and their children turned up here at all odd hours to discuss something or the other and he welcomed them with warm feelings.”

Today, all that can be seen of the original Vihara is a prayer or meditation hall. A peepul tree that was planted just behind the hall has grown to impressive proportions. There are statues of the Buddha and one of Ambedkar, and the Bahujan Vihar Trust offices are also on the premises.

It is true that there is no mention of Dharmanand anywhere on the premises today, and the person there who seemed to be in charge was not aware of Dharmanand Kosambi or his contribution to the establishment of the Vihāra.

There is a plaque of recent provenance which says that the historic Buddha Vihara was consecrated by the footfall (पदस्पर्शाने) of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar who, on the Thursday evenings when he would stay at the Rajgriha Dadar, would come along with his wife to worship the Buddha and to meditate. The Buddha Vihara, according to this plaque, was inaugurated on 4th April 1938.

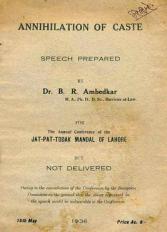

As it happens, his role in the establishment of this vihāra seems to have been indirect. On October 13, 1935, at the site now termed the Muktibhumi in Yeola, Babasaheb Ambedkar made the emphatic public announcement, “I was born a Hindu, but will not die a Hindu” to reject caste (just a year before Annihilation of Caste would be written). After the publication of Hindi Sanskriti ani Ahimsa in December 1935 by Kosambi, Ambedkar had had some discussion about Buddhism with him. Although Ambedkar would only formally adopt Buddhism twenty years hence, it was clear that he was deeply attracted to Buddhist philosophy and thought. For Dharmanand, Buddhism was more than a faith. Ever since he had met Iyothee Dass in Madras in the early 1900’s, he knew that this was a way of liberation from caste, that it possibly held answers to resolving a host of social ills. The combination of socialism and spirituality appealed to him more than the implementation of Marxism that he had seen in the USSR some years earlier.

Gail Omvedt, in her biography of Ambedkar, sees the events unfolding differently. “Kosambi met Ambedkar in October 1935, and immediately afterwards went to discuss the issue of conversion with Gandhi. Ambedkar, he told Gandhi, was close to Buddhism, and asked for funds to build a Buddhist vihar in Parel. Gandhi immediately turned to Jugalkishor Birla, sitting nearby, who presented Kosambi with a cheque for Rs 17,500. Out of this came plans for a ‘Bahujan Buddhist Bihar’ in Parel. But an initial meeting was broken up primarily out of rivalry between two Chambhar leaders, Sitaram Shivtarkar, who was taking part in the meeting, and his opponent Balkrishna Deorukhkar. In any event, nothing came of the Bahujan vihar, perhaps because Ambedkar was not ready to throw his support to anything financed by Gandhian money.”

Bits and pieces of this might well be factually correct, except that the conversation was between Gandhi and Kosambi and Ambedkar was not directly involved, and further, something did come of the Bahujan Vihara. The meeting between Ambedkar and Kosambi was in 1936, and that between Kosambi, JK Birla and Gandhi was probably in 1936, and it is very likely that the Vihara was ready by January 1937.

I suspect that the plan to make the Bahujan Vihara was largely Dharmanand’s social experiment, and would have started in 1935 or 1936, based on Sawkar’s chronology which comes in large part from her conversations with her grandmother. There is something to be said for family memory when there is so little documentation. In Gandhi’s daily diaries, there are no records of Dharmanand meeting him in 1935; an entry for 4 August, 1936 says that “Dharmanand Kosambi and Abdul Gaffar Khan called on Gandhi”, but the construction of the Vihara might have already started by then.

By 1939, Dharmanand would dissociate himself from the Vihāra, and according to Meera Kosambi this was in reaction to JK Birla’s criticism of some statements in Hindi Sanskriti ani Ahimsa. There may be more to this, given Dharmanand’s inability to stay in any one place for very long. The interactions between Gandhi, Ambedkar, Kosambi, and even Birla, were not simple: their private and public positions played out in the background of the freedom movement where they all were all on the same side, but there were caste tensions as well as opposing philosophical positions and vastly disparate economic positions as well. Ambedkar and Dharmanand took to Buddhism for different reasons. The debate on caste between Gandhi and Ambedkar is well known even today. Birla would support the construction of any number of religious buildings, but as a member of the Hindu Mahasabha, his motives would be viewed with some degree of suspicion by both Dharmanand or Ambedkar, again for different reasons.

Dharmanand’s philosophy was in some ways very innocent. Having translated the Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosa he was seized with the mission to communicate this in as simple a manner as he could to as many people as he could reach. He therefore wrote Samadhimarg or The Path of Meditation in 1925, a do-it-yourself manual in Marathi. In addition to information about the purpose of samadhi, Dharmanand discusses factors that promote or prevent successful samadhi, sprinkled with relevant anecdotes from Buddhist literature. As Meera Kosambi says in The Essential Writings, even while Dharmanand “saw the urgent need to introduce the common man to this means of obtaining peace in a world increasingly caught up in a feverish whirl of activity — from various types of entertainment to diverse expressions of nationalism — he doubted whether it was within the latter’s intellectual and philosophical grasp. Finally he was encouraged by the example of the renowned Gandhian, Kishori Lal Mashruwala who had lived for several months in solitude before rejoining Gujarat Vidyapeeth as its Principal and resuming his work for the education and enlightenment of the common man. It was to Mashruwala that Dharmanand dedicated the book as a token of his admiration.”

In 1926, when DD Kosambi was an undergrad at Harvard, one of his stated projects was to translate Samādhimarg to English, French and German, but nothing came of this in the next forty years. Last week I was in Pune and managed to get a copy of the Marathi text from among the books left behind in the Kosambi family library. This is a bit of a long term project, but here is a text that needs translation, if not into German and French, into English at the very least. It would be a fitting tribute to all three Kosambis, Dharmanand, Damodar, and Meera.

One of DD Kosambi’s last articles was a paper submitted to Scientific American entitled

One of DD Kosambi’s last articles was a paper submitted to Scientific American entitled  Further correspondence, and a visit to the Fogg, threw up some more details. I had conjectured that the coins were likely to be from either Portuguese India (of which he was then a citizen) or British India (where the family was then living) so it came as quite a surprise to me to learn that the records at Fogg indicated that these were “26 Indian silver coins from date of

Further correspondence, and a visit to the Fogg, threw up some more details. I had conjectured that the coins were likely to be from either Portuguese India (of which he was then a citizen) or British India (where the family was then living) so it came as quite a surprise to me to learn that the records at Fogg indicated that these were “26 Indian silver coins from date of

D D Kosambi

D D Kosambi The family house is still standing, home today to the

The family house is still standing, home today to the

A week ago I was in Chikli/Chikhali and with the photograph in Sawkar’s book and more than a little luck I was able to track down the Lad house. Like the Kosambi home in Sankhwal, it is no longer with the descendants of the Lads, but it is in utter ruin, the roof having caved in some time ago, so all one can see is the bare outline of what must once have been an imposing structure. The house is large, and one can imagine that it once commanded quite a view of the lands that the Lads owned, and probably a view of the Chapora river as well.

A week ago I was in Chikli/Chikhali and with the photograph in Sawkar’s book and more than a little luck I was able to track down the Lad house. Like the Kosambi home in Sankhwal, it is no longer with the descendants of the Lads, but it is in utter ruin, the roof having caved in some time ago, so all one can see is the bare outline of what must once have been an imposing structure. The house is large, and one can imagine that it once commanded quite a view of the lands that the Lads owned, and probably a view of the Chapora river as well.

I thought I had made a complete bibliography of

I thought I had made a complete bibliography of

Dharmanand passed at 2:30 pm on 4 June, with Balvantsinha in attendance. “At about 12 noon, he said that he was now about to depart. At 2 p.m., he drank a little water and asked me to open all the doors, as though someone had come to carry him away and the doors had to be kept open for them to pass out. He had never before requested me to keep the doors open. The throb of life in his body gradually slackened and he expired exactly at 2:30. Between the moment till which he continued to speak in full consciousness and the time he drew his last breath, there was not more than ten minutes’ interval.”

Dharmanand passed at 2:30 pm on 4 June, with Balvantsinha in attendance. “At about 12 noon, he said that he was now about to depart. At 2 p.m., he drank a little water and asked me to open all the doors, as though someone had come to carry him away and the doors had to be kept open for them to pass out. He had never before requested me to keep the doors open. The throb of life in his body gradually slackened and he expired exactly at 2:30. Between the moment till which he continued to speak in full consciousness and the time he drew his last breath, there was not more than ten minutes’ interval.”