The sociologists Gita Chadha (then at Mumbai University) and Renny Thomas (at IISER Bhopal) have edited a new collection of essays in Science and Technology Studies (or STS), Mapping Scientific Method: Disciplinary Narrations where they asked a large number of academics to write about the methods that are intrinsic to their disciplines. As Renny put it, this […] volume aims at building a discussion around how the scientific method finds different expressions in different disciplines. We do think that the question of method cannot be divorced from the larger cultures in and of science.

The sociologists Gita Chadha (then at Mumbai University) and Renny Thomas (at IISER Bhopal) have edited a new collection of essays in Science and Technology Studies (or STS), Mapping Scientific Method: Disciplinary Narrations where they asked a large number of academics to write about the methods that are intrinsic to their disciplines. As Renny put it, this […] volume aims at building a discussion around how the scientific method finds different expressions in different disciplines. We do think that the question of method cannot be divorced from the larger cultures in and of science.

When they invited me to contribute to their intended chapter on Chemistry, I was – to put it mildly – more than a little uncertain as to what to write and how. For one thing, I have meandered among various formal disciplines (judging, say, by the journals I have published in, at any rate). Given that my principal interest has been in Chaos Theory and its applications, this meandering has been, predictably, whimsical and unpredictable… But Chemistry is indeed the discipline wherein I earned all my degrees, so I felt I should give it a shot.

TBH though, my first shot fell short of the mark, and the editors suggested that instead of a formal essay, it might work better if they were to have a conversation with me. An edited version of the transcript of that conversation, titled On Method, Techniques, and Scale is excerpted below. For convenience I have coloured their questions in blue, and my responses are in black.

RT: Ram, thank you for agreeing to do this conversation with us. Can we start by looking back at your early education and training in chemistry? Do you remember any courses on methods that you undertook as a bachelor’s or even master’s student of science? We find that the teaching of method is not central in disciplinary training, especially in the natural sciences.

RR: I was an undergraduate student at Loyola College in Madras in the 1970’s. Then or now, methodology, as you say, is not actually taught or discussed explicitly in most undergraduate science programmes such as the BSc in Physics, Chemistry, or Maths. There were things that we were taught as a matter of course, with no particular emphasis on methodology. Even at the master’s level, I would say it wasn’t as if we were welcomed with a philosophical introduction to the why and how of the methods that would be employed in the discipline. A lot of students in India make career choices when they are very young, and these choices are restricted by the streams of science, arts, and commerce. There are not many options. Things might change now that we have the NEP 2020 (The National Education Policy of India, 2020, emphasises the integration of the liberal arts with the science-centric streams in Higher Education Institutions) but at that time in 1969, I went to college and decided that I was going to do a BSc in chemistry – with not very clear ideas about why I wanted to do it. And then I followed whatever we were taught. On reflection, I would say that we learned a lot of techniques, and in effect the practice: the technique – is or becomes – the method for us.

RR: I was an undergraduate student at Loyola College in Madras in the 1970’s. Then or now, methodology, as you say, is not actually taught or discussed explicitly in most undergraduate science programmes such as the BSc in Physics, Chemistry, or Maths. There were things that we were taught as a matter of course, with no particular emphasis on methodology. Even at the master’s level, I would say it wasn’t as if we were welcomed with a philosophical introduction to the why and how of the methods that would be employed in the discipline. A lot of students in India make career choices when they are very young, and these choices are restricted by the streams of science, arts, and commerce. There are not many options. Things might change now that we have the NEP 2020 (The National Education Policy of India, 2020, emphasises the integration of the liberal arts with the science-centric streams in Higher Education Institutions) but at that time in 1969, I went to college and decided that I was going to do a BSc in chemistry – with not very clear ideas about why I wanted to do it. And then I followed whatever we were taught. On reflection, I would say that we learned a lot of techniques, and in effect the practice: the technique – is or becomes – the method for us.

Chemistry experiments in laboratories, especially in the undergraduate curriculum, were fairly basic. We were taught how to analyse compounds and mixtures, how to do assays by titration – how to identify molecules, how to identify their composition, how to identify the amount, and then, as we learned a little more in the second year and the third years we got a chance to synthesise molecules. And a lot of that was very ‘how to’ – the method was the instruction. Or the instruction was the method, in the sense that we were told ‘add so many grams of this to so much of that, observe what happens’ and so on. So we learned a lot of the methodology by doing.

GC: How does theory get taught? We suppose that theory and methods are linked, aren’t they? So, is there something like a concept of theory, in the curriculum, at this stage?

RR: I’ve been talking to younger colleagues who tell me that increasingly the practical aspect of chemistry is getting lost in our country. In many universities, practical laboratory experiments are not carried out or are not emphasised at any rate. That’s why some of these newer, smaller universities, and smaller science universities such as the Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISERs) are important because at least they give students a chance to learn the subject as it is, or as we learned it. In many of our public institutions, the experimental part of chemistry is increasingly de-emphasised.

Hence, in these contexts, the learning of theory happens in two ways. One, in the absence of experiments, all of chemistry is or becomes ‘theory’. But that’s not the theory we are talking about, right? Second, in most contexts, one takes things in good faith – because we cannot go around repeating and verifying everything. So when a teacher comes in and tells you there are so many elements in nature, or that this piece of glass is actually a liquid and not a solid, one accepts it as the theoretical truth. Many of these things work on a certain kind of faith, which can be paradoxical because we are supposed to teach our students to question – particularly in the sciences. There’s a limit up to which the questions are tolerated or can be encouraged.

RT: In many of these places, are ‘practicals’ – which are basically laboratory experiments – seen as an alternative to the active teaching of methods, and probably also of theory?

RR: In the best places, we do have the ‘practicals’, many of which are fairly routine. And the routine of it emphasises the method if you like. Even today when you measure the viral load in a COVID patient, to give a current context, one does this via an assay, essentially a titration, and in principle not very different from what you might have done when you were a 16- or 17-year-old, measuring the amount of acid in a solution. The tools have changed, the techniques have changed, but the ‘method’ is the same. And in a sense, it contains the theory too.

RT: If we look at the history of science, it’s clear that the discipline of chemistry has had a strong foundation in the experimental method. Yet we don’t find discussions on method in chemistry, unlike, for example, in physics and astronomy. Is there a particular reason for that?

RR: Well, I don’t know. As a subject, chemistry is the one with the strongest connection to experiment, because it all begins with fire, in some sense. The first repeatable experiment that we as humans have ever been able to do is to set fire to things and to know what is combustible and what is not. These are the original questions of what is the constitution of matter. An early experiment would have figured out that water doesn’t burn and dried leaves do, and so on, so the constituents of matter were all discovered only through early experiments. We wouldn’t call these experiments in the modern sense of course, but I see them as being valuable precursors to experiments, because they were always practical and chemistry has, in this sense, a strong experimental tradition.

RR: Well, I don’t know. As a subject, chemistry is the one with the strongest connection to experiment, because it all begins with fire, in some sense. The first repeatable experiment that we as humans have ever been able to do is to set fire to things and to know what is combustible and what is not. These are the original questions of what is the constitution of matter. An early experiment would have figured out that water doesn’t burn and dried leaves do, and so on, so the constituents of matter were all discovered only through early experiments. We wouldn’t call these experiments in the modern sense of course, but I see them as being valuable precursors to experiments, because they were always practical and chemistry has, in this sense, a strong experimental tradition.

But in chemistry, there is also the question of scale. There is something about the sheer size of certain numbers that chemistry has to grapple with that makes it very difficult to think in terms of detailed, mechanistic ideas of method.

GC: Could you elaborate?

RR: See, chemists talk about molecules and atoms, and when you ask how many atoms are there in a cube of ice, it is of the order of Avogadro’s number, which is about a billion billion million, such a mind-bogglingly large number. So the basic unit that a chemist works with, the molecule, is much much smaller than the scale of the typical experiment. I believe that this is one of the reasons why the connection to theory or the connection to method becomes difficult. I think that the question of scale is one that chemists have to grapple with all the time.

GC: So, you’re trying to explain a very vast field in terms of something very small, is that the problem?

RR: Absolutely. Though this is not the only subject with that problem, a lot of subjects have the same issue. But chemistry is also a somewhat ‘centrally’ located subject because of the kinds of questions it is trying to look at. The basic unit in chemistry is really the molecular scale. And since you’re doing experiments involving typically 1023 molecules – some 23 powers of 10 above that – it is one of the reasons why some of the methodological concepts can be difficult.

RT: That is interesting. Often one thinks that chemistry as a ‘discipline’, a body of knowledge about matter, which sets the parameters for the experimental method – but which disappears and loses its identity in the sciences. It becomes associated as the foundation of ‘methods’ in other scientific disciplines, like biology for instance but loses its place as a theoretical discipline with its own understanding of matter. Is there a reason why it is difficult to distinguish between ‘chemistry as a discipline’ and ‘chemistry as method’? It would be interesting to know if this happens as part of the training of a chemist. Any pedagogic or historical reasons that you might think of? Is it good and advantageous to have such a thin line between discipline and method?

RR: One aim of the laboratory chemist is to make specific molecules, to engineer substances with desired properties. For them, it’s also internal: the practice is the method, as I said. There is a goal and one does not think in terms of whether it is a discipline or whether it is a bunch of methods. What happens as a part of your training is learning the important questions that need to be asked. For the chemist there are certain types of questions that are paramount, one of which can be paraphrased as follows: Given a molecule or given a property that is required (or desired) the aim of the practical scientist is ‘Can I achieve that particular property?’ Take, for example, LEDs that emit white light, or LEDs that emit red or green light. So one might want, say, a blue LED, and one can do this in many different ways. The chemist would approach the objective thinking ‘Can I make a molecule that would emit blue?’ Whereas a physicist might turn around and say, ‘Can I put enough pressure or can I somehow change the physical conditions of the system so that I can achieve the same thing?’ Meaning, the chemist would be led automatically to achieve his/her engineering of the situation by changing the molecule that they are playing around with, whereas the physicist might be more inclined to change the conditions around which the thing is operating. Of course, that distinction is blurred because today you have to ask what the material scientist is doing, and that person might like to do both. Another caricatured kind of thinking that guides, let’s say, the practical chemist is the manner in which drugs are designed. If one came up with a molecule, let us say, that could kill the flu virus, and you know that the SARS virus is similar in shape, so the chemist might start by changing the molecule around, change its shape, or what have you, and see if it can kill the SARS virus.

In short, the aim is to do what one can by manipulating the things that I know best, namely small- or medium-sized molecules. Molecular biology also deals with molecules, it just happens to be very big molecules.

Specialisations, Theory, and Histories

RT: Ram, in chemistry the distinction between inorganic and organic chemistry has emerged historically and has become widespread. We have different departments for these two specialisations in some institutions. Does this divide reflect institutional, historical, methodological, or even ideological/political needs?

RR: The answer is: to varying degrees, all of the above. The way in which the chemistry departments grew in Europe, in the middle 1800s, say, was really along the lines of the kinds of molecules that people looked at. One of the facts of life, as far as chemistry is concerned, is that most molecules that occur naturally, so-called natural products tend to have a preponderance of carbon atoms. It was erroneously thought that life was needed in order to create such molecules, hence the adjective organic. From the early 1800s though it was recognised that there was nothing organic about such molecules that contained carbon, although there are special features of carbon that make such compounds interesting from various points of view. It also happens that many organic molecules have industrial applications. All of pharmaceutical chemistry, the pharma industry, and medicinal chemistry, eventually also dyes, drugs, petrochemicals, all these dealt with essentially organic molecules, and therefore it was almost natural that when you have so much interest in all this, you have a Department of Organic Chemistry. Inorganic chemistry then got defined by exclusion, more or less, but over the past decades it has been widely realised that such a distinction does not really make much sense.

Most of these distinctions were made in universities and institutions outside India, and by and large we mirrored these here – there was not much by way of turf here in developing a subject. As a matter of fact the only department which was somewhat unusual and new is the Solid State and Structural Chemistry unit at the IISc, and there is probably no such department elsewhere in the world. I suppose one starts defining a new sub-discipline, there is not much that is methodological. There are some instances of entire departments of Physical Chemistry and/or Analytical chemistry, but these are rare, mercifully. By and large the unity of the discipline is emphasised within most departments.

RT: You have already answered parts of our next question which is related to what we asked you in the beginning too. Where do we locate theoretical chemistry in our discussion on methods? The reason we also ask this question is because while theoretical physicists enjoy a dominant, and even higher, epistemological status in institutes of fundamental research – such as the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) or Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) – in India, theoretical chemists don’t. Does this distinction between theoretical vs applied/or experimental have to do with different methods in the two disciplines? Or is it something else?

RR: The big distinction between theoretical physics and theoretical chemistry (and I know that a lot of theoretical physicists will disagree with me on this) is that a theoretical chemist has to work very closely with an experimental chemist. If you don’t, the theory is not worth all that much. This is not as crucial in theoretical physics.

To give an example, I was a postdoc with a well-known theoretical chemist, Rudolph Marcus who got the Nobel Prize for his very important theory of electron transfer. This theory of electron transfer applies to how materials corrode, how oxidation happens, some of the crucial steps in photosynthesis – electron transfer is everywhere. Marcus came up with his idea in the late 1950s and 1960s, and there was an assumption that he had to make. The theory was applied from the beginning and was widely used, but he only got the Nobel Prize in 1992 because it was only in the middle 1980s that a very crucial result of his assumption – the so-called Marcus inverted regime – was experimentally verified. There is some similarity to Higgs, who was given the Prize only after the discovery of the Higgs particle, but nobody had any doubt that there was a Higgs particle. Even if it had somewhat different properties, most physicists would concur that the Higgs boson was a very real entity. As also gravitational waves. Maybe I don’t understand these issues very well, but my impression is that fundamentally people did not disbelieve in the existence of the Higgs particle. But this is not the same thing when it comes to belief or disbelief of theory in chemistry.

In a way, there are few conceptual frontiers that remain in chemistry – at least not in the same manner as there are in physics – so even the theory is to a large extent ‘applied’.

Intuition, Innovations, and the Silos

RT: We are also keen to explore the nature of the creative process in the method of science. If we look at the history of innovations in chemistry, some of the innovations were products of what we may call ‘serendipity’. But then serendipity is not seen as a crucial element in the production of scientific knowledge. As a practising chemist, how do you view this debate?

RR: Many accomplished chemists that I have met or interacted with are great masters of intuition. And that comes from a lot of experience, from repeatedly looking at a problem. Many chemists think in pictures, so there’s a lot of very strong intuition that gets built up through this practice. Very fine chemists build up their repertoire by just seeing example after example after example, and then that serendipitous discovery comes about. It could not happen in the absence of a wealth of experience. A young graduate student walking into his or her lab and discovering something absolutely new and wonderful – that does not happen easily in this field.

GC: The word intuition is used very differently by scientist across different fields and disciplines, isn’t it? The mathematicians understand intuition very differently from, say the physicists. Within physics, the theoretical physicist understands it differently from the experimentalist. So if we really want to look at the question of intuition, it would actually make sense to see how the scientists themselves are looking at intuition. Anyway, Ram, also, how do we contest – or nuance – this popular idea of the ‘eureka moment’ in scientific discoveries where insights are believed to come out of nowhere?

RR: No, it does not come out of anywhere! Regardless of discipline, it has to be grounded in some experience. The people whom I would class as being intuitive are really people who have spent a fair amount of intellectual time thinking about very specific kinds of issues. For example, the question of what is the shape that a molecule might take, or what shape a group of molecules might take? Large molecules for which the answer is not immediately obvious. This is related to problems like protein folding, which in turn is related to things like how the ribosome acts and similar questions. Even a casual conversation with someone who thinks deeply about such matters would tell you that the intuition was based on (a) a lot of examples that they have seen, and (b) obsession. That is, you’ve got to keep on thinking about a problem over and over again, in different contexts and so on, and then you may get your flash of insight. But of course, that moment took it’s time coming. That moment was actually built up of a lot of other moments.

GC: Right. The trouble comes in the pedagogy of science, or what we call the meta-narrative of science in society, where on the one hand science is presented as a rational and linear method, on the other hand there is a drama around how genius discoveries are made, and how they rely on exceptional talent often associated with the great intuition of individual scientists.

RR: I think as academics, particularly as practising academics, we try to convey that our subject is interesting. I used to frequently have discussions with my mother and she would be asking me questions like, ‘What do you actually do?’, ‘Is it satisfying to just sit in your office?’ She was not really able to understand the how of it – her job was a practical one, taking things from one place to another, doing specific tasks, going somewhere, and she couldn’t understand what it was that I did. This kind of incomprehension is quite common – most people just don’t get it. So in an effort to make our work interesting, we talk mainly about the high points, the grand ideas. But very frequently when I mentor young students I try to explain to them that a lot of science is boring. It’s boring in the sense in which you think certain things are boring – repetitive without very spectacular occurrences every day. As we grow older, we do realise that a lot of what we do just takes a lot of time, is repetitive, and is not particularly insightful. But, we gloss over these facts.

GC: Yes, and when we want to present it, we want to present it in this very hyper-glamorised way, very dramatic, and almost mystified manner.

RR: Exactly! I mean, one can’t say ‘I went to the lab, I worked from morning to evening. Not sure I made any progress.’ What’s there to say about your typical working day, right?

GC: Yes. It’s interesting that you put it in this way. Because often we sociologists are asked by our friends in natural sciences: ‘What do you actually do in sociology?’ The fact that we do ‘field work’ – or formal and abstract work sometimes – and not laboratory work is never good enough!

RR: I taught at JNU for 30 odd years and many STEM colleagues did not really appreciate the need for a School of International Studies. Or that social science colleagues would be away from their workplaces in the afternoon to consult archives or to do field work? I exaggerate a little, but only a little. This attitude was not uncommon.

Language, Grammar, and Culture

RT: The next set of questions are about language, Ram. It would be interesting to hear your views on the question of language in chemistry – its methods and its larger pedagogic context?

RR: Well, I haven’t thought so much about it because I’ve grown up in the English language tradition of Indian education. I did learn German because I thought it would be useful for me as a chemist and that I could read some of the texts in the language they got written in. I actually did, I studied German in (undergraduate) college and had to pass an exam to qualify for my PhD. Many US universities did have a foreign language requirement even in the 1970s. But it has not been useful anymore because even the Germans write in English these days! But, more in our context in India, especially given the huge difficulty that many of us have with English, I think that many science subjects are, in fact, somewhat intimidating to non-native speakers of English. The ‘natural’ language of a science or of a discipline can sometimes be very off-putting, because the nuances are lost in the learning and non-native speakers don’t pick up as much.

I’ve seen this happen in JNU and have been concerned about this in the language of examinations, for instance. When setting a national examination that is given to let’s say, 200,000 aspirants – all of whom are thinking in different languages – the manner in which a question is framed can itself be very intimidating.

RT: And alienating.

RR: Yes, alienating and off-putting. As it happens I’m grappling with this issue now, and in formulating questions, I try to imagine how a person who thinks in Hindi or in Tamil is going to see the way in which the question is phrased.

GC: We would like you to dwell a little more on this question, especially in the way it pans across the silos. Some of us in the social sciences tend to think that this question of language, this problem of language faced by many a student in India is graver in the social sciences and the humanities. And that in the sciences it’s probably less so because science is mathematical, uses symbolic conventions. So, in that sense, a functional knowledge of English is sufficient. What do you think of this?

RR: I think that is a bit of an illusion. Thanks to JNU, I have had several students who are first-generation learners. First generation, but coming from remote districts of India. Being a first-generation learner in Dharavi is very different from being a first-generation learner who’s coming out of Champaran or someplace like that. In one case, you may not have education at home, but many of your neighbours are educated. But what do you do when your entire village is uneducated? And somehow you have aspirations and you manage to come to university…

RR: I think that is a bit of an illusion. Thanks to JNU, I have had several students who are first-generation learners. First generation, but coming from remote districts of India. Being a first-generation learner in Dharavi is very different from being a first-generation learner who’s coming out of Champaran or someplace like that. In one case, you may not have education at home, but many of your neighbours are educated. But what do you do when your entire village is uneducated? And somehow you have aspirations and you manage to come to university…

I have students whose lack of English has been such a major handicap: in spite of their ability to work phenomenally hard, sometimes they just don’t understand. Science is also built up on jargon and on tradition. So it’s not as if one can just get away with a rudimentary knowledge of English. Sometimes, the best contribution I am able to do to a collaboration is to reformulate an idea. In a sense, just by changing the language, one can give something additional to the concept. And that is true in science as well as in any other discipline.

GC: Do you think that the language of modern chemistry is Eurocentric? Can we say that? Would you say that? This is a provocative and polemical question, but we cannot escape asking it

RR: It is Eurocentric, but so is much of the language of all of science.

GC: It’s almost a grammar that we’ve inherited, right, a culture of that grammar and also a cultural grammar?

RR: We’ve inherited a grammar but we’ve not been able to steal that grammar, to make it our own. We’ve not even been able to create a creole!

GC: Or reinvent it? Hybridise it?

RR: We have created a tradition of sorts in mathematics, in the way in which a lot of the inventive mathematics was done in the subcontinent, so it can be done. But most of Indian science, and I will be massacred for saying it, is really quite derivative. It is derivative either by mimicry, in the sense that you look at what has been published in the latest journal and then you ask related questions in your own context. Or it is derivative by tradition, what you did for your postdoctoral training in a research group elsewhere, you continue to do for the rest of your career. I don’t think that we’ve created a new indigenous tradition – what I am calling a creole – through this process.

GC: It’s possible though, you think?

RR: Of course, it is possible. Japan for example has its own idiom, as does China. I lived in Japan for a while and I know that it is possible to do science in Japanese. It is not really possible to do much science in Hindi or Bangla or any other Indian language. Eventually you’ll just have to come back to English.

GC: Yes, while on the one hand we have so many dialects and diverse languages on the other the dominant languages, often the official ones, are deeply embedded in caste and other social structures of power. For instance, the kind of regional translations that are available in the social sciences is extremely sanskritised and brahmanical. They reproduce another hegemonic order and culture, don’t they?

RR: There used to be this joke that in the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR)’s Mathematics department, the faculty meetings could be conducted in Tamil.

RT: Upper caste Tamil! But let’s link this to the question of access. The question of language is central in understanding caste and gender-based exclusions in India. Recent attempts to teach engineering in Telugu, or Kannada, in some engineering colleges in the South, have met with resistance from the Dalit and Bahujan communities. While many local politicians have welcomed these moves to ‘indigenise’, there is a large resistance from Dalit and Bahujan intellectuals because they see English as the language of emancipation for their people. We must also see this in the context of the larger patterns that are emerging with the privatisation of higher education in India. While the privileged upper caste students go to elite colleges – and will study in English – in the city, students from the rural areas will be forced to study in their ‘mother tongue’. Consequently, the upper caste elites will continue to dominate these professions because of their English skills.

RR: Exactly! Who’s going to employ them? This is a serious concern. The discussion on language is very difficult in our country and it’s fraught with all sorts of problems, but, if we are to internalise it to make an idiom which is truly somehow non-western, truly somehow ‘ours’, it has to be done. Otherwise, you are just a derivative. If your only source of information is (the magazine) Nature, or Science, or another of the fancy journals, then you’ve already lost. In a lot of our institutions, the main focus of publications is really not to address a problem of relevance, but to do something that will use the correct jargon and get into Nature.

One of the brightest students at JNU who was admitted to virtually every PhD programme he applied for in the country (he could not afford the cost of going abroad) nevertheless chose to join the DAE for the assured job it gave him. When making this choice, he basically told me that his family could not afford having him not contributing for another five or six years.

GC: Let us examine the language – academic language across the silos – question further. You’ve been the Vice Chancellor of one of the leading central universities of the country, the University of Hyderabad, and you have had experiences with JNU another Central University with a rich culture of dissent. You have this vast experience of being an academic administrator and also of being a public intellectual; all of that. Typically, our experience has been that in a conversation between the scientist and the social scientist, the latter is often accused of using jargon. The scientist tends to think that everything that a social scientist says should be accessible to them, simply because they understand English, and because it is all common sense in any case. How do you see this? Isn’t this epistemic intolerance a very serious problem when we are attempting to go beyond the silos? How do we educate ourselves? And challenge Snow’s assumptions of the two cultures that shall never meet

RR: This happens even in a pluralistic university like JNU, one which is very sensitive to democratic ideals.

RT: And progressive.

RR: And progressive, but not in all ways. There are political positions that are actually very strange, for example, many of my colleagues from the social sciences would say that the ‘science-types’ are all right wing, no question: if you are from a science school, then you must be right wing and today of course it goes along with a particular kind of ideology. Many of them actually seriously believe it. I used to find that offensive.

But this is very much a case of the two cultures. What was true of Cambridge in Snow’s time was true of JNU too. Scientists on the faculty had a very poor understanding of what scholarship in the social sciences actually meant. And sadly, most of the good scholars in the humanities and social sciences did not engage with their peers in the sciences as equals. Maybe it was the fact that most of the science faculty were not very sophisticated on political and cultural issues, or maybe because as far as they were concerned the science-wallahs were interested in some mundane issues and small questions, not in something grand in scope or importance.

I was aware that JNU was well known as a social sciences university because of the stellar contributions that had been made in those areas, and the people who had been there. But most of these contributions of JNU could not be quantified in the same way as the contribution from the sciences could. The science contributions were straightforward to measure: how many papers have you written, where have they appeared, how many people have cited them, and so on. Social science contributions would focus on the number of books, the impact on policy, the seminars attended, and so on. Similar, but different.

So when I went to Hyderabad, one of the things that I was conscious of was these very different yardsticks by which to evaluate disciplines. I believe the JNU experience made me quite sensitive to the fact that contributions from different disciplines come in different packages. And, at some point, one has to go beyond the numbers, and also to realise that peer validation and peer recognition can be a very real way of evaluating contribution. If a whole group of people whom I believe are serious academics, tell me that someone is a fine young sociologist, then I don’t have to sit in further judgment and ask for the h-index data as well.

GC: In fact, quite a few of the social scientists in Hyderabad University say that this is something that really helped them in your tenure as Vice Chancellor, you strove to delink measures that were used for the social sciences from those that were used for the natural sciences.

RR: I think that it is useful to have some recognition that people can aspire for, especially at the early stages of one’s academic career. You must have noticed that in India there are a lot of awards for ‘young’ scientists and very few for social scientists. So one of the things I was able to introduce at the University of Hyderabad was a set of early career awards that were actually open to all disciplines, with different modes of evaluation for different areas.

RT: As we conclude, a very generic question but a question that brings us back to the question of method. What is going to be the future of chemistry as a discipline? More particularly, do you think chemistry as a discipline has to rethink its methods? If yes, what are some of the methodological challenges the discipline of chemistry will have to deal with in the coming future?

RR: I’m probably not the best person to answer this. But if I were to essay a response, I’d say that one of the things that will increase in importance in chemistry is the notion of complexity. The reductionist approach that is characteristic of much of modern science is changing. What we’ve realised at least in the last couple of decades is that systems are complex and the reductionist approach is not always possible. When dealing with large (very large!) numbers of molecules, it can be very profitable to factor in features such as cooperativity and to look at the system as a whole.

Chemists have been doing this for some time already – the realisation that one can use the idea of groups of molecules as a fundamental unit rather than just using atoms and molecules is dawning on many chemists. If I may make an analogy with your discipline, if instead of the individual being the important constituent, one might think about a family, or a clan or a tribe – as the basic unit. This ‘supra’ molecular approach gives a very different way of thinking about how to carry out chemical processes. Similarly, one increasingly sees that instead of carrying out a set of reactions sequentially, it is possible to carefully manipulate the chemical environment in a reaction vessel so as to make the system effectively control the outcome. This is where intuition comes in, knowing how to manipulate the circumstances to get a desired chemical outcome. Let me just say in a catch-all terminology that a recognition of complexity and factoring it in is an important way in which this subject is evolving.

Institutions, Excellence, and Exclusions

RT: Let us, in this last section, shift somewhat to questions of scientific communities and cultures. And examine how objective and inclusive these are. In the Indian context, for instance, rarely does one see scientists publicly talk about caste and gender, leave alone an easy entry into the domain. As a scientist who is interested in sociological questions in science, what are your observations on the discipline of chemistry itself? Would you say it is dominated by upper-caste, Hindu, Brahmins? At least in the elite institutions. What are the possibilities of democratising the discipline of chemistry in India?

GC: Also, in the hierarchy of sciences and if you examine them on the axes of purity–impurity, what we see is the hierarchy of sciences. The ‘pure sciences’ are at the top. And what are the pure sciences? They are abstract, they are theoretical, the queen being mathematics. Disciplines like chemistry which are much messier are placed lower down in this hierarchy of abstraction and purity. You have the hierarchy between the pure and the applied and experimental, even within disciplines. This phenomenon recurs in the social sciences too. How do you respond to this?

RR: These are some of the issues that have come to the forefront recently, the democratisation of science. We have to learn how to do it better, and learn how to do it fast.

Actually, a proper answer to this would need much more thinking on my part, but let me tell you my immediate thoughts. The fact that most faculty members in most departments are savarna is just a consequence of the fact that only the savarnas have had access to higher education by large. Dalits have a much more difficult time coming into education and being able to do science is even more of a challenge.

That said, the establishment, namely us, has not taken this as a solvable challenge, at least not in the way that gender disparity is seen as a solvable challenge. Namely that it is possible to get equal numbers of women and men into science, it is possible to keep the percentage of women working in science to something like 40%, and so on. By and large, people see this as something that can be achieved.

Some years ago, I tried to get information from the Indian Academy of Sciences about the composition of the summer research fellows that they support each year. Out of something like 20,000 students who applied for a summer fellowship, what are the different categories that students fall into? Most often one can figure out gender from the name, but caste and religion are much more difficult. And there’s a backlash against even trying to collect this information: Although there have not been many studies on this matter, when asked, many Indian scientists would claim to be atheist and non-casteist, and even caste blind. In this context, asking about religion or caste can be a challenge.

The fact of the matter is that we have not really given access. It is not enough just to assert that one’s doors are open, one has also to make sure that others can enter. From the word go, we have excluded entire categories by imposing impossibly high standards. By the time someone from less privileged backgrounds is even able to contribute, they have to climb against a huge gradient. What I guess I’m trying to say is that unless we try hard to give proper access at the entry stages to different groups, we will not see any change in the composition of departments. We need to work hard in order to make our institutions truly representative of our social diversity.

Another thing that works against inclusivity is the small numbers that we admit into higher education. Especially in our elite institutions, there is the attitude of exclusivity that communicates ‘What I do is very difficult – you can’t work with me, you won’t be able to keep up’. And this leads to small numbers of students that these faculty are able to mentor. In a career of 30 or so years (which is fairly typical), if I happen to have one student, or two or three, chances are they’ll also be savarna, and the consequence is that the composition of the academic pool doesn’t change as fast as it needs to. On the other side of the spectrum, at some universities it is possible to mentor a larger number of students (I’m talking about PhD mentorship) – something like one per year, so in a career of 35 years one could have had about that many students. Were they all brilliant? No. But over the years, it doesn’t matter – they all have positions, and the effect of the training tells. And in those 35, there were students from reserved categories, there were students from different religions, from a large number of states, there were women. Even so, this was not as representative as it should have been. When the numbers are large enough, this level of diversity almost comes for free.

GC: This despite the original discouragement of being told and made to feel that this science stuff, particularly the abstract and theoretical stuff is too difficult, and complicated. ‘And just too hard for someone like you’.

RR: Yes, ‘It’s too hard, you won’t be able to do anything significant … and you won’t get a job after that. You know you have to support your family’. This kind of apparently realistic mentoring is in effect very discouraging.

Moving from TIFR to JNU saved me in a sense, because at TIFR I could have lived out my working years quite peacefully. I may not have had more than five or ten students, if at all, because TIFR works that way. That was actually the major motivation for me to get out of TIFR because I realised that the longer I stayed there, the more difficult it was going to be for me to have students of my own. Having been educated in the United States, the US University was the model that in my mind was worth emulating. That’s how you did things: you had your own research group, own grants, own research problems.

Moving from TIFR to JNU saved me in a sense, because at TIFR I could have lived out my working years quite peacefully. I may not have had more than five or ten students, if at all, because TIFR works that way. That was actually the major motivation for me to get out of TIFR because I realised that the longer I stayed there, the more difficult it was going to be for me to have students of my own. Having been educated in the United States, the US University was the model that in my mind was worth emulating. That’s how you did things: you had your own research group, own grants, own research problems.

The best thing that happened to me was that by coming to JNU, I got this independence. I have also very consciously never turned away a student and have quite consciously tried to help them reach whatever level they could, telling them in effect that the quality of their PhD would be as good as they could make it. The point of mentorship is to help the student achieve their goals to whatever extent, and this is something that I really internalised at JNU. Many of the leading social scientists were really exemplary in this regard.

GC: Could this also be because of the divide between the research institutes, the so-called centres of excellence, and the universities, the former set-up exclusively for reassert and the latter for teaching, once again a problematic divide that sets up hierarchies?

RR: Yes! Absolutely.

RT: So, do you think that the university could be the site for a re-imagination and reinvention of quality education and research? And not these centres of excellence? We seem to be putting so much of a premium on these centres of excellence.

RR: What is happening also is that these so-called centres of excellence will realise that they have to become more university-like. Look at what is happening already in TIFR and the new national laboratories. They realise that they have to get out of their exclusivity which is so much at variance with the rest of the ethos of the country. They are somehow upholding a standard that is truly not representative. Much of what they do is an elitist pursuit of elitist ideals, which are in the long run, unsustainable.

I believe that we will see many of these institutions – if they are not able to become more like universities, that is to have more students and more turnaround, with the vitality that comes from the flow – we will see them wither away. When I came back from the USA, that was a higher education model that I knew, it was also a model that I admired. I did not find myself admiring the actual conditions in TIFR, although to be honest, what’s not to like? I mean the exclusive West Canteen, the magnificent art collection, the dramatic setting by the sea, the manicured lawns and gardens … Yet I left TIFR in 1986, very clear that this level of exclusivity was something I did not want.

GC: Ram, let us look at your own social location more reflexively. You were born in an upper-caste, upper-class family. Was your choice to do science influenced by these social locations?

RR: In the late 1960s there were few disciplinary choices available. I didn’t have biology in school, so medicine was out, and I had little interest inmost other fields. But I did have the freedom to choose what I did, and that came from the fact that I belonged to an upper-middle-class family.

GC: Being male and heterosexual gives you a further advantage. Were you conscious of these advantages in your early life, maybe even as child?

RR: I don’t think I realised all this at the time, but I was aware that I had the luxury of pursuing an academic career because there was no pressure on me, from my parents or others in the family, to take up a professional career (or a ‘well-paying’ job).

GC: Also, do you think these structural privileges helped you gain the power and success you did? Recognising privilege is a step in the direction of making scientific cultures more inclusive. How did you learn to do that?

RR: At some point, I did articulate to myself (and a few others) that the biggest gift that I got from my parents was this freedom to do what I wanted. Several of my contemporaries did not have this luxury – they had to start earning earlier, had to have more well-defined career paths, they had a responsibility to their families. I see that now with several of my students, and the choices that they have had to make. A first-generation learner who has the freedom to pursue a PhD has a very different sense of what he or she ‘owes’ to those that in a very real sense made it possible. Being from a privileged background makes one much less sensitive to this matter.

RR: At some point, I did articulate to myself (and a few others) that the biggest gift that I got from my parents was this freedom to do what I wanted. Several of my contemporaries did not have this luxury – they had to start earning earlier, had to have more well-defined career paths, they had a responsibility to their families. I see that now with several of my students, and the choices that they have had to make. A first-generation learner who has the freedom to pursue a PhD has a very different sense of what he or she ‘owes’ to those that in a very real sense made it possible. Being from a privileged background makes one much less sensitive to this matter.

GC: Ram, at the very end we want you to address a rather sticky debate in the relationship between science and society. What do you think is the relationship between scientific method and the scientific temper? We think that the former is a very specific academic tool used by the sciences and that it varies so much in practice. We think that it cannot be applied as a corrective to all social and cultural belief patterns. Science, or its method, cannot always serve as an antidote to the unreason of various kinds, can it? In fact, science often reproduces social hierarchies, like when it justifies racial, caste, or gender inequalities. We’d suggest that a more powerful epistemic and moral tool is required to counter unreason in our world, science is not enough, and neither is scientific temper. A critical temper of enquiry, wherever it comes from, needs to be promoted. What do you think?

RR: Like many of us, I am not overly fond of the term (scientific temper) nor do I think that years of scientific practice makes it even possible to clearly define what this temper is. The use of the word temper in this phrase is both subtle and unfortunate. Subtle because it is uncommonly used in this context, and therefore minute distinctions need to be made between temper and temperament. It is unfortunate because of the implied arrogation of all wisdom or knowledge of a truth to science and its methods.

There is much wisdom in the adage that the more one knows, the more one needs to know, and that is more zen than the scientific method.

GC: Ram, thank you very much for this conversation […] on several important issues not only about the method of science as it travels in and from chemistry, but also about how this scientific method does or does not find its way into larger scientific cultures and practices. It was also important to speak about the problems of going beyond methodological silos.

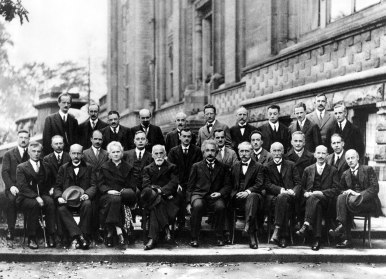

When the first Solvay Conference was organized in 1911 to discuss current problems in Physics and Chemistry, Marie Curie was the only woman invited. It probably took her 1903 Nobel prize in physics to secure her place at the table, though in all fairness, many (but not all) of the men there were Nobel laureates.

When the first Solvay Conference was organized in 1911 to discuss current problems in Physics and Chemistry, Marie Curie was the only woman invited. It probably took her 1903 Nobel prize in physics to secure her place at the table, though in all fairness, many (but not all) of the men there were Nobel laureates. Sixteen years later, when the fifth Solvay was held in 1927, she still was the only woman at the meeting although by then she had her second Nobel prize (in chemistry, in 1911). There were some other women who might have been invited to the meeting on quantum physics – Lise Meitner had been appointed Professor of Physics in Berlin in 1926 (she would go on to discover nuclear fission) and the mathematician Emmy Noether who made seminal contributions in mathematical physics. There may have been others as well, but the bar had been set high: the next woman to be awarded the Nobel prize in physics was Maria Goeppert-Mayer, in 1963…

Sixteen years later, when the fifth Solvay was held in 1927, she still was the only woman at the meeting although by then she had her second Nobel prize (in chemistry, in 1911). There were some other women who might have been invited to the meeting on quantum physics – Lise Meitner had been appointed Professor of Physics in Berlin in 1926 (she would go on to discover nuclear fission) and the mathematician Emmy Noether who made seminal contributions in mathematical physics. There may have been others as well, but the bar had been set high: the next woman to be awarded the Nobel prize in physics was Maria Goeppert-Mayer, in 1963… But this post is mainly about a Conference and some Workshops that will be held in the coming week that relate to this issue. The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (or IUPAP) which in some sense represents physicists worldwide decided to create a Women in Physics (WiP) Working Group (WG5) in 1999 with the main aim being to suggest means to “improve the situation for women in physics. Since this is a global organization, the hope was to use the strength of numbers to address an issue that did not seem to change over the years

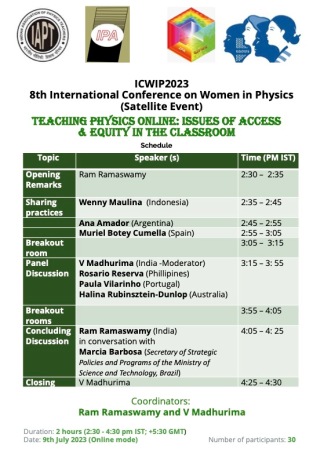

But this post is mainly about a Conference and some Workshops that will be held in the coming week that relate to this issue. The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (or IUPAP) which in some sense represents physicists worldwide decided to create a Women in Physics (WiP) Working Group (WG5) in 1999 with the main aim being to suggest means to “improve the situation for women in physics. Since this is a global organization, the hope was to use the strength of numbers to address an issue that did not seem to change over the years WG5 has taken more onto its plate and now this group is also given the task of suggesting means to increase gender diversity and inclusion in the practice of physics and to promote and take actions to increase gender diversity and inclusion across countries and regions. One of the outcomes of the general global awareness was the creation of the Gender in Physics Working Group (GIPWG) of Indian Physics Association (IPA), the main moving force behind the push to bring this conference to India.

WG5 has taken more onto its plate and now this group is also given the task of suggesting means to increase gender diversity and inclusion in the practice of physics and to promote and take actions to increase gender diversity and inclusion across countries and regions. One of the outcomes of the general global awareness was the creation of the Gender in Physics Working Group (GIPWG) of Indian Physics Association (IPA), the main moving force behind the push to bring this conference to India. Teaching Physics Online: Issues of Access & Equity in the Classroom will be an online meeting from 2:30-4:30 pm IST on Sunday, 9th July. Since the theme for the International Women’s Day 2023 was specified by the UN to be DigitAll – Innovation and technology for gender equality, this seemed like a good discussion point, especially since already before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe, education was leaning towards online modes through the use of MOOCs. Post-pandemic, online education is here to stay. In India, this is reflected in the National Education Policy 2020 which has a large online education component. On the one hand there is a noticeable gender inequity in access to digital devices and internet, and on the other hand, the amount of time available to women teachers (and students) is restricted by societal norms.

Teaching Physics Online: Issues of Access & Equity in the Classroom will be an online meeting from 2:30-4:30 pm IST on Sunday, 9th July. Since the theme for the International Women’s Day 2023 was specified by the UN to be DigitAll – Innovation and technology for gender equality, this seemed like a good discussion point, especially since already before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe, education was leaning towards online modes through the use of MOOCs. Post-pandemic, online education is here to stay. In India, this is reflected in the National Education Policy 2020 which has a large online education component. On the one hand there is a noticeable gender inequity in access to digital devices and internet, and on the other hand, the amount of time available to women teachers (and students) is restricted by societal norms. I’ve written about DFOT on this blog before, but one thing we thought was whether we could use the occasion of ICWIP to have a discussion with physics teachers in India on just how effective the online medium can be when there is no pandemic to worry about, and what the gender dimension is in practice. On the 8th of July, we will have a Workshop on Teaching Physics Effectively Online an in-person meeting at GITAM. Teachers who are participating in the discussion include Bindu Bambah, Rukmani Mohanta, Barilong Mawlong (all from the University of Hyderabad), Venkatesh Chopella (IIIT) Meenakshi Viswanathan (BITS-Pilani) and Sai Preeti (GITAM). There will also be a hybrid lecture by Vandana Sharma of the IIT Hyderabad on Imaging assisting Humankind: Fundamental Science to Application and hopefully there will be a link to the online talk here.

I’ve written about DFOT on this blog before, but one thing we thought was whether we could use the occasion of ICWIP to have a discussion with physics teachers in India on just how effective the online medium can be when there is no pandemic to worry about, and what the gender dimension is in practice. On the 8th of July, we will have a Workshop on Teaching Physics Effectively Online an in-person meeting at GITAM. Teachers who are participating in the discussion include Bindu Bambah, Rukmani Mohanta, Barilong Mawlong (all from the University of Hyderabad), Venkatesh Chopella (IIIT) Meenakshi Viswanathan (BITS-Pilani) and Sai Preeti (GITAM). There will also be a hybrid lecture by Vandana Sharma of the IIT Hyderabad on Imaging assisting Humankind: Fundamental Science to Application and hopefully there will be a link to the online talk here.

The sociologists Gita Chadha (then at Mumbai University) and Renny Thomas (at IISER Bhopal) have edited a new collection of essays in Science and Technology Studies (or STS),

The sociologists Gita Chadha (then at Mumbai University) and Renny Thomas (at IISER Bhopal) have edited a new collection of essays in Science and Technology Studies (or STS), RR: I was an undergraduate student at Loyola College in Madras in the 1970’s. Then or now, methodology, as you say, is not actually taught or discussed explicitly in most undergraduate science programmes such as the BSc in Physics, Chemistry, or Maths. There were things that we were taught as a matter of course, with no particular emphasis on methodology. Even at the master’s level, I would say it wasn’t as if we were welcomed with a philosophical introduction to the why and how of the methods that would be employed in the discipline. A lot of students in India make career choices when they are very young, and these choices are restricted by the streams of science, arts, and commerce. There are not many options. Things might change now that we have the NEP 2020

RR: I was an undergraduate student at Loyola College in Madras in the 1970’s. Then or now, methodology, as you say, is not actually taught or discussed explicitly in most undergraduate science programmes such as the BSc in Physics, Chemistry, or Maths. There were things that we were taught as a matter of course, with no particular emphasis on methodology. Even at the master’s level, I would say it wasn’t as if we were welcomed with a philosophical introduction to the why and how of the methods that would be employed in the discipline. A lot of students in India make career choices when they are very young, and these choices are restricted by the streams of science, arts, and commerce. There are not many options. Things might change now that we have the NEP 2020 RR: Well, I don’t know. As a subject, chemistry is the one with the strongest connection to experiment, because it all begins with fire, in some sense. The first repeatable experiment that we as humans have ever been able to do is to set fire to things and to know what is combustible and what is not. These are the original questions of what is the constitution of matter. An early experiment would have figured out that water doesn’t burn and dried leaves do, and so on, so the constituents of matter were all discovered only through early experiments. We wouldn’t call these experiments in the modern sense of course, but I see them as being valuable precursors to experiments, because they were always practical and chemistry has, in this sense, a strong experimental tradition.

RR: Well, I don’t know. As a subject, chemistry is the one with the strongest connection to experiment, because it all begins with fire, in some sense. The first repeatable experiment that we as humans have ever been able to do is to set fire to things and to know what is combustible and what is not. These are the original questions of what is the constitution of matter. An early experiment would have figured out that water doesn’t burn and dried leaves do, and so on, so the constituents of matter were all discovered only through early experiments. We wouldn’t call these experiments in the modern sense of course, but I see them as being valuable precursors to experiments, because they were always practical and chemistry has, in this sense, a strong experimental tradition. RR: I think that is a bit of an illusion. Thanks to JNU, I have had several students who are first-generation learners. First generation, but coming from remote districts of India. Being a first-generation learner in Dharavi is very different from being a first-generation learner who’s coming out of Champaran or someplace like that. In one case, you may not have education at home, but many of your neighbours are educated. But what do you do when your entire village is uneducated? And somehow you have aspirations and you manage to come to university…

RR: I think that is a bit of an illusion. Thanks to JNU, I have had several students who are first-generation learners. First generation, but coming from remote districts of India. Being a first-generation learner in Dharavi is very different from being a first-generation learner who’s coming out of Champaran or someplace like that. In one case, you may not have education at home, but many of your neighbours are educated. But what do you do when your entire village is uneducated? And somehow you have aspirations and you manage to come to university… Moving from TIFR to JNU saved me in a sense, because at TIFR I could have lived out my working years quite peacefully. I may not have had more than five or ten students, if at all, because TIFR works that way. That was actually the major motivation for me to get out of TIFR because I realised that the longer I stayed there, the more difficult it was going to be for me to have students of my own. Having been educated in the United States, the US University was the model that in my mind was worth emulating. That’s how you did things: you had your own research group, own grants, own research problems.

Moving from TIFR to JNU saved me in a sense, because at TIFR I could have lived out my working years quite peacefully. I may not have had more than five or ten students, if at all, because TIFR works that way. That was actually the major motivation for me to get out of TIFR because I realised that the longer I stayed there, the more difficult it was going to be for me to have students of my own. Having been educated in the United States, the US University was the model that in my mind was worth emulating. That’s how you did things: you had your own research group, own grants, own research problems. RR: At some point, I did articulate to myself (and a few others) that the biggest gift that I got from my parents was this freedom to do what I wanted. Several of my contemporaries did not have this luxury – they had to start earning earlier, had to have more well-defined career paths, they had a responsibility to their families. I see that now with several of my students, and the choices that they have had to make. A first-generation learner who has the freedom to pursue a PhD has a very different sense of what he or she ‘owes’ to those that in a very real sense made it possible. Being from a privileged background makes one much less sensitive to this matter.

RR: At some point, I did articulate to myself (and a few others) that the biggest gift that I got from my parents was this freedom to do what I wanted. Several of my contemporaries did not have this luxury – they had to start earning earlier, had to have more well-defined career paths, they had a responsibility to their families. I see that now with several of my students, and the choices that they have had to make. A first-generation learner who has the freedom to pursue a PhD has a very different sense of what he or she ‘owes’ to those that in a very real sense made it possible. Being from a privileged background makes one much less sensitive to this matter.

We asked a group of teachers and students as to how they were reacting to the shift to online teaching. Different subjects, different kinds of institutions, different geographical locations… Some attempt to capture the diversity of the academic landscape in India. The resulting twenty essays were published online in

We asked a group of teachers and students as to how they were reacting to the shift to online teaching. Different subjects, different kinds of institutions, different geographical locations… Some attempt to capture the diversity of the academic landscape in India. The resulting twenty essays were published online in

In brief, the impact of the virus on higher education has

In brief, the impact of the virus on higher education has  The cynical view – that we will all simply go back to the way we were before this, India can never change, etc. etc. – is simply untenable. The virus has exposed several faultlines in the way we have been doing things so far, and if nothing else, the past few months have underscored that there is much in India that needs to change. As I mentioned in an

The cynical view – that we will all simply go back to the way we were before this, India can never change, etc. etc. – is simply untenable. The virus has exposed several faultlines in the way we have been doing things so far, and if nothing else, the past few months have underscored that there is much in India that needs to change. As I mentioned in an  There was no option – here or anywhere else in the world for that matter – but to shut colleges and universities. Given our ignorance of the disease, our inability to cope with large numbers of the affected, it was necessary to put the brakes on large gatherings. That has also immediately communicated the severity of the problem to all of us very directly, and the ever increasing numbers of the “confirmed positive” drive home the point that there was good reason to be concerned. This is a real danger: no one is insulated from the virus by wealth or by privilege. Nearly one in 12 who gets the disease succumbs and getting the disease is so much a matter of chance, there are few guarantees… All we really know is avoidance: Wear masks, wash hands, isolate. Wash hands, isolate. Repeat.

There was no option – here or anywhere else in the world for that matter – but to shut colleges and universities. Given our ignorance of the disease, our inability to cope with large numbers of the affected, it was necessary to put the brakes on large gatherings. That has also immediately communicated the severity of the problem to all of us very directly, and the ever increasing numbers of the “confirmed positive” drive home the point that there was good reason to be concerned. This is a real danger: no one is insulated from the virus by wealth or by privilege. Nearly one in 12 who gets the disease succumbs and getting the disease is so much a matter of chance, there are few guarantees… All we really know is avoidance: Wear masks, wash hands, isolate. Wash hands, isolate. Repeat.

I have stopped relying on serendipity; this has been replaced over the years by a firm belief in the hidden hand that unbeknownst to me puts things in my way, gives subtle signs, and guides me forward.

I have stopped relying on serendipity; this has been replaced over the years by a firm belief in the hidden hand that unbeknownst to me puts things in my way, gives subtle signs, and guides me forward.

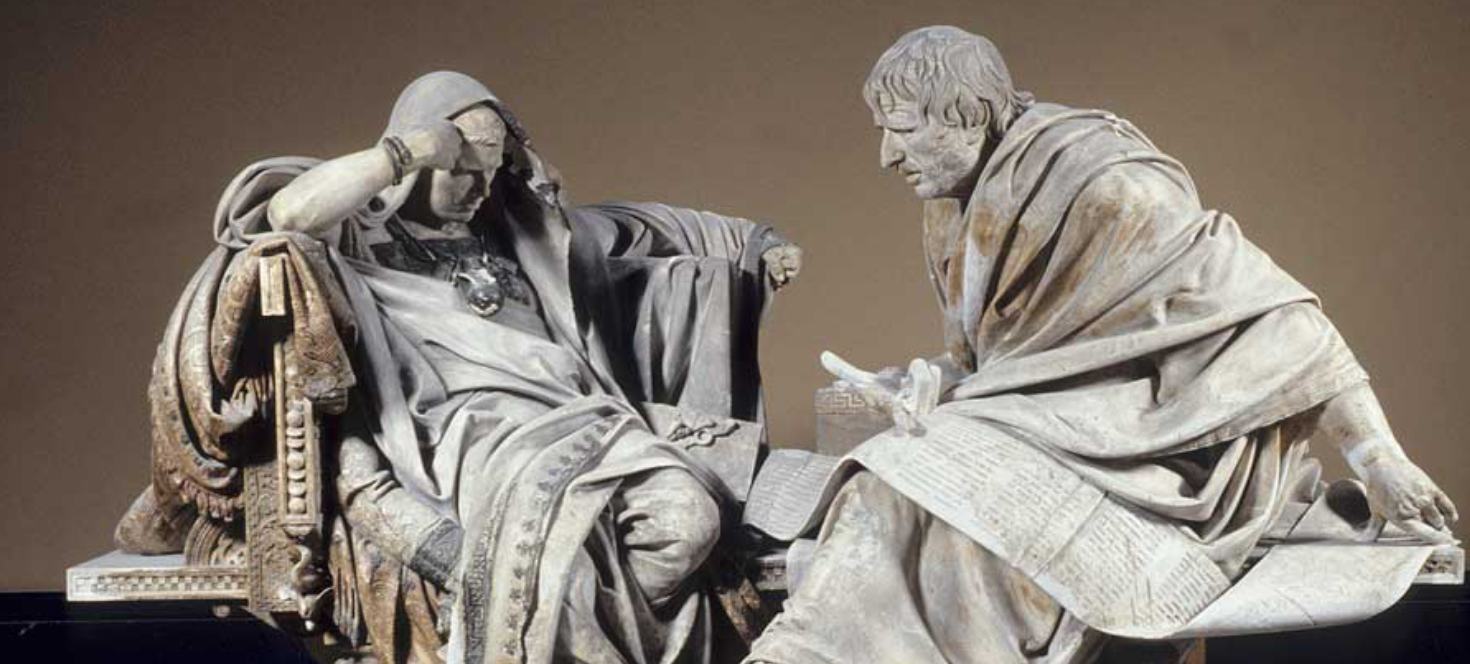

Seneca’s own life was so filled with contradictions that he was quite attuned to the fickleness of fortune and very sensitive to the whims of successive Roman Emperors, at least two of who – Caligula and Nero – who had ordered him to commit suicide… Therefore let the mind be disciplined to understand and to endure its own lot, and let it have the knowledge that there is nothing which fortune does not dare – that she has the same jurisdiction over empires as over emperors, the same power over cities as over the citizens who dwell therein. We must not cry out at any of these calamities. Into such a world have we entered, and under such laws do we live. If you like it, obey; if not, depart whithersoever you wish. Cry out in anger if any unfair measures are taken with reference to you individually; but if this inevitable law is binding upon the highest and the lowest alike, be reconciled to fate, by which all things are dissolved.

Seneca’s own life was so filled with contradictions that he was quite attuned to the fickleness of fortune and very sensitive to the whims of successive Roman Emperors, at least two of who – Caligula and Nero – who had ordered him to commit suicide… Therefore let the mind be disciplined to understand and to endure its own lot, and let it have the knowledge that there is nothing which fortune does not dare – that she has the same jurisdiction over empires as over emperors, the same power over cities as over the citizens who dwell therein. We must not cry out at any of these calamities. Into such a world have we entered, and under such laws do we live. If you like it, obey; if not, depart whithersoever you wish. Cry out in anger if any unfair measures are taken with reference to you individually; but if this inevitable law is binding upon the highest and the lowest alike, be reconciled to fate, by which all things are dissolved.

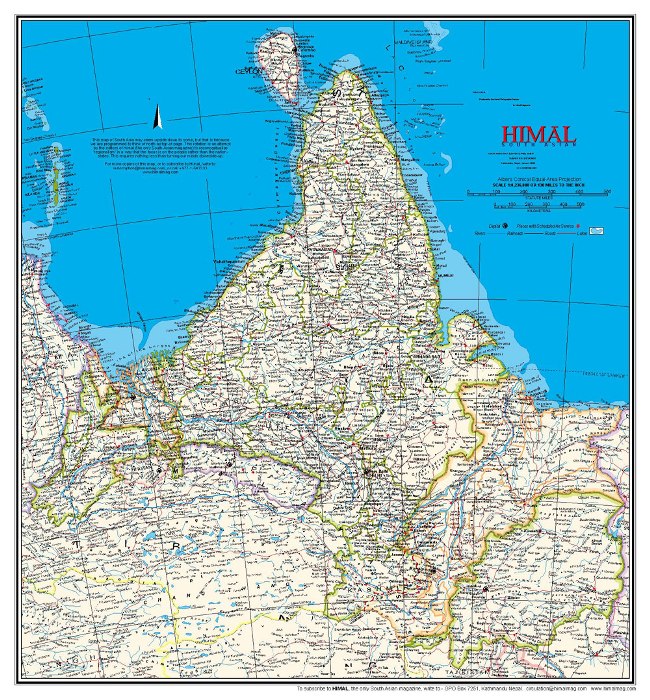

We are taught – those of us who have learned of the physical world – that there is no special place in space from which one should derive all our coordinates. There really is no preferred sense of direction other than by convention and by legacy. For many years now, I have had the Himal South Asia magazine’s unusual map hanging in my office and have had innumerable discussions (of a non-political kind) about how it helps to change one’s point of view about our country, whats up south and down north and so on. I must say that learning to see this map every working day (and learning to refer to it in as normal a fashion as possible) has also been instructive in its own way, and it seems more natural now to draw a line from Kanyakumari down to Kashmir rather than the other way around. To have any sense of nationalism hinge on a completely arbitrary definition of up or down is to have a somewhat unhinged sense of nationalism.

We are taught – those of us who have learned of the physical world – that there is no special place in space from which one should derive all our coordinates. There really is no preferred sense of direction other than by convention and by legacy. For many years now, I have had the Himal South Asia magazine’s unusual map hanging in my office and have had innumerable discussions (of a non-political kind) about how it helps to change one’s point of view about our country, whats up south and down north and so on. I must say that learning to see this map every working day (and learning to refer to it in as normal a fashion as possible) has also been instructive in its own way, and it seems more natural now to draw a line from Kanyakumari down to Kashmir rather than the other way around. To have any sense of nationalism hinge on a completely arbitrary definition of up or down is to have a somewhat unhinged sense of nationalism. And speaking of ultra-leftist, another thing that hangs in my office is (what I consider) a superb poster, a telescopic image of Ché Guevara on the South American continent… something I picked up forty years ago when it was fresh and new, and another thing I have had to explain to any number of visitors who eventually all come down to “Ah… JNU, what else can one expect?” But this is just one poster, and it is more about the kind of aesthetic I cared about at some point in time rather than some ideology that is indelibly tattooed onto my soul.

And speaking of ultra-leftist, another thing that hangs in my office is (what I consider) a superb poster, a telescopic image of Ché Guevara on the South American continent… something I picked up forty years ago when it was fresh and new, and another thing I have had to explain to any number of visitors who eventually all come down to “Ah… JNU, what else can one expect?” But this is just one poster, and it is more about the kind of aesthetic I cared about at some point in time rather than some ideology that is indelibly tattooed onto my soul.

There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the

There is no gainsaying that this is an important matter, and a difficult one to address in a wholly satisfactory manner, especially in a multilingual country like ours, one where the general level of education is not as high as one would like. Nevertheless, one must laud efforts that have a non-negligible impact, and the  There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the

There is a sense in which the privilege of being invested in to pursue publicly funded research is very much an expression of the  The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant

The friendship and the intense discussions between Goethe and Humboldt, for instance, as Andrea Wulf discusses in her brilliant  One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.

One can go on talking about talking about science… but in the end the basic points are few. There needs to be much more about scientific matters in public discourse, particularly in this day and age, when almost any aspect of our daily life is so influenced by the scientific advances of the past few centuries. It has always needed science communicators (who may or may not be practicing scientists) to do their bit, to bring out the significance of the work, and to see where value can be added. But hearing about any field directly from the ones who have contributed to its advance – in whatever way – has a charm and value all of its own.