In retrospect, it seemed a simple enough idea then.

The Women in Science panel of the Indian Academy of Sciences felt that a good way of inspiring young women to a career in science would be to have role models that they could look up to. During a brainstorming session at the Academy in 2005 or 2006, the panel (of which I was then an informal member) converged onto the opinion that these role models should be found from within the cohort of women scientists living and working in India – after all, the WiS panel itself, with Rohini Godbole as the first Chair, was the result of an earlier committee on “Women in Science” that the IASc had formed in 2003, after the fact that women were an underrepresented minority in science became startlingly apparent to the wider community… Why it took so long (and why is the situation still far from satisfactory) is a matter to be discussed in another post, but still. One recommendation of that committee was the creation of a Panel for “Women in Science” (WiS) that could carry on the work of building a more equitable representation of academics in science.

The Women in Science panel of the Indian Academy of Sciences felt that a good way of inspiring young women to a career in science would be to have role models that they could look up to. During a brainstorming session at the Academy in 2005 or 2006, the panel (of which I was then an informal member) converged onto the opinion that these role models should be found from within the cohort of women scientists living and working in India – after all, the WiS panel itself, with Rohini Godbole as the first Chair, was the result of an earlier committee on “Women in Science” that the IASc had formed in 2003, after the fact that women were an underrepresented minority in science became startlingly apparent to the wider community… Why it took so long (and why is the situation still far from satisfactory) is a matter to be discussed in another post, but still. One recommendation of that committee was the creation of a Panel for “Women in Science” (WiS) that could carry on the work of building a more equitable representation of academics in science.

Among the various initiatives of the WiS panel were a number of outreach activities, intended to sensitise the public at large to societal issues that kept women from making a career in science – parental pressures, the attitude of teachers (that women cannot or should not do science) and so on. As we were to find out, we had much to learn.

Around that time, K.R. Sreenivasan, then Director of the International Center for Theoretical Physics, Trieste put together One Hundred Reasons to be a Scientist, a collection of essays by about a hundred highly reputed scientists from all over the world shared what attracted them to science as youngsters and kept their interest alive. This seemed like a good model to follow: get together a group of women scientists who had made a mark professionally, and ask them to tell their stories in their own words. What was their journey on the path of science, the passions that helped keep the motivation from flagging, the tribulations that they underwent and did not mind talking about, and what had helped, as well as what did not, career-wise.

Around that time, K.R. Sreenivasan, then Director of the International Center for Theoretical Physics, Trieste put together One Hundred Reasons to be a Scientist, a collection of essays by about a hundred highly reputed scientists from all over the world shared what attracted them to science as youngsters and kept their interest alive. This seemed like a good model to follow: get together a group of women scientists who had made a mark professionally, and ask them to tell their stories in their own words. What was their journey on the path of science, the passions that helped keep the motivation from flagging, the tribulations that they underwent and did not mind talking about, and what had helped, as well as what did not, career-wise.

The first idea was to emulate 100 Reasons and put together a collection of biographical sketches of influential Indian women scientists of earlier generations, to underline the fact that it is possible to find role models within the country. We (namely Rohini and myself) further felt that it was important, especially for young girls with research ambitions, to know of women who functioned and achieved their goals in the Indian social and academic environment. So Anandibai Joshee, India’s first western educated medical practitioner, was a choice, as was Janaki Ammal, the first Fellow of the Academy and a distinguished plant biologist. And others.

But we also felt that it was important to to emphasise the importance of science to the individual, while also making the choice of a career in science a fairly “ordinary” one – there was nothing exceptional about a woman choosing to be a scientist.

So we decided to combine these ideas and have a section on women of an earlier generation and another on those who were currently working in STEM. For the former we invited suggestions from colleagues in a wide variety of disciplines, and for the latter we invited about two hundred working women scientists in India, using a combination of objective and subjective criteria, to write about their personal journeys. Therefore we asked our contributors to give some idea of the journey on the path of science – the passions that help keep the motivation strong, the tribulations they might have undergone. We had also asked them to talk about what helped in their careers, as well as what did not. We wanted to mirror our cultural and regional diversity, and to cover a range of disciplines so that any student could gain from the insights and experiences of these women to whom they might have been able to relate at many levels.

The response that we got was overwhelming. There was enthusiasm: many women colleagues were keen to share their experiences. Some did not choose to write, but gave important advice. And there were some who did not respond.

When the dust settled, we had about one hundred essays in all, and after a certain amount of editorial effort, the book Lilavati’s Daughters: The Women Scientists of India (edited by Rohini Godbole and Ram Ramaswamy) was finally published and released in 2008 in New Delhi, at the Annual Meeting of the Academy that was held that year in IIT Delhi.

When the dust settled, we had about one hundred essays in all, and after a certain amount of editorial effort, the book Lilavati’s Daughters: The Women Scientists of India (edited by Rohini Godbole and Ram Ramaswamy) was finally published and released in 2008 in New Delhi, at the Annual Meeting of the Academy that was held that year in IIT Delhi.

The book had global impact almost immediately, with reviews appearing in Nature, C&E News and a number of newspapers in India. This is almost surely not a complete list.

About the name. After the book was reviewed in Nature we wrote a short letter to the journal to mention that the inspiration came from the title of Bhaskara’s twelfth century mathematical treatise, Lilavati. Bhaskaracharya (1114–85) an author of several texts, was a mathematician and astronomer and a teacher of repute. “The name Lilavati, which literally means ‘playful’, is a surprising title for an early scientific book. Some of the mathematical problems posed in the book are in verse form, and are addressed to a girl, the eponymous Lilavati.

However, there is little real evidence concerning Lilavati’s historicity. Tradition holds that she was Bhaskaracharya’s daughter and that he wrote the treatise to console her after an accident that left her unable to marry. But this could be a later interpolation, as the idea was first mentioned in a Persian commentary. An alternative view has it that Lilavati was married at an inauspicious time and was widowed shortly afterwards.

However, there is little real evidence concerning Lilavati’s historicity. Tradition holds that she was Bhaskaracharya’s daughter and that he wrote the treatise to console her after an accident that left her unable to marry. But this could be a later interpolation, as the idea was first mentioned in a Persian commentary. An alternative view has it that Lilavati was married at an inauspicious time and was widowed shortly afterwards.

Other sources have implied that Lilavati was Bhaskaracharya’s wife, or even one of his students — raising the possibility that women in parts of the Indian subcontinent could have participated in higher education as early as eight centuries ago.

However, given that Bhaskara was a poet and pedagogue, it is also possible that he chose to address his mathematical problems to a doe-eyed girl simply as a whimsical and charming literary device.”

Much more should not be read into the choice of the name. What is more important is, as we noted in the preface to the first edition, is that “the women scientists who eventually featured in Lilavati’s Daughters gave generously of themselves, sharing their stories with candour and with warmth. The set of nearly one hundred essays gives some flavour of what it takes to be a woman scientist in India today. Negotiating through the diversity of cultures, regional distinctions, languages, and traditions in order to pursue a career in science has its complexities. It was both interesting and instructive to learn from these narratives that achieving a balance between family and career was just one of the many challenges in the journey of several of our contributors!”

That was more than fifteen years ago, and since then we have had to reprint the book some five times, bringing the total print run to about 14,000 copies. Most of these have been given away to students, researchers, and libraries since outreach was the main aim, but it was also available in select bookstores, and now is available for purchase by the general public here as well.

There are editions of LD in Malayalam (Leelavathiyude Penmakkal, 2013, Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishath, Thrissur), and partial translations into Marathi (Loksatta, 2009, Vidynayanmayee Series, Chaturang Supplement), Hindi (Shaikshanik Sandarbh, 2009, 2010 (volumes 63 – 67), Eklavya, Bhopal), Kannada (Ganitashastradalli Minchida Mahileyaru, 2012, Karnataka Rajya Vijnana Parishat, chapters 20–28) and Gujarati (Sandarbh, 2011, Nachiketa and ARCH (Action Research in Community Health)).

There are editions of LD in Malayalam (Leelavathiyude Penmakkal, 2013, Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishath, Thrissur), and partial translations into Marathi (Loksatta, 2009, Vidynayanmayee Series, Chaturang Supplement), Hindi (Shaikshanik Sandarbh, 2009, 2010 (volumes 63 – 67), Eklavya, Bhopal), Kannada (Ganitashastradalli Minchida Mahileyaru, 2012, Karnataka Rajya Vijnana Parishat, chapters 20–28) and Gujarati (Sandarbh, 2011, Nachiketa and ARCH (Action Research in Community Health)).

In collaboration with Mandakini Dubey, we brought out a different shorter version of LD meant for a younger audience, “A Girl’s Guide to a Life in Science” (GGLS) in 2012. The essays included there were extended to include a description of the scientific field as well; GGLS is a joint publication of the Indian Academy of Sciences and Zubaan, New Delhi. The book has also been translated into Telugu, Vignanashastra Rangamlo Mahila Sphoorthipradatalu (Emesco Books, Vijaywada, 2013).

In collaboration with Mandakini Dubey, we brought out a different shorter version of LD meant for a younger audience, “A Girl’s Guide to a Life in Science” (GGLS) in 2012. The essays included there were extended to include a description of the scientific field as well; GGLS is a joint publication of the Indian Academy of Sciences and Zubaan, New Delhi. The book has also been translated into Telugu, Vignanashastra Rangamlo Mahila Sphoorthipradatalu (Emesco Books, Vijaywada, 2013).

LD has a presence on social media as well, on FaceBook, entries in Wikipedia in English as well as a few Indian languages. An indication of the extent to which LD has penetrated popular culture came from an unexpected source. In the 12th season of the hugely popular television game show, Kaun Banega Crorepati (the Indian version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire?) the penultimate question in the 43rd episode (in December 2020) was “Lilavati’s Daughters, a book published by IASc, Bengaluru features about 100 essays on which of these groups of people?” The four choices were

LD has a presence on social media as well, on FaceBook, entries in Wikipedia in English as well as a few Indian languages. An indication of the extent to which LD has penetrated popular culture came from an unexpected source. In the 12th season of the hugely popular television game show, Kaun Banega Crorepati (the Indian version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire?) the penultimate question in the 43rd episode (in December 2020) was “Lilavati’s Daughters, a book published by IASc, Bengaluru features about 100 essays on which of these groups of people?” The four choices were

A. Indian Women scientists

B. Indian Women Historians

C. Indian Women Architects

D. Indian Women Poets

The contestant – who happened to be a woman – went on to win the contest after answering this question correctly!

This post is occasioned by the release of the second edition of LD which gave us the opportunity of updating the original preface to include some developments particularly to do with translations into several Indian languages. We also updated the profiles of all the contributors. In addition we also include two new biographies in the second edition, those of Bibha Chowdhuri (1913–1991) and Leela Mulherkar (1915–2005), pioneers in the areas of experimental particle physics and developmental biology respectively.

When they started in 2005, the WiS panel has had a difficult course to chart. Then – and for that matter, even now – the number of women Fellows of the Academy was below 10% of the total Fellowship. Although women had been in the Academy right from the beginning – E.K. Janaki Ammal was a Foundation Fellow of the Academy, elected in 1935 (in contrast, the Royal Society formed in London in 1660 first admitted women in 1945, and the French Academy of Sciences, founded in 1666 would wait till 1979 to have its first female member). But the numbers only grew very very slowly: the (smoothed) graph on the right shows just how slow the change was. The second woman Fellow was elected in 1960, the third in 1962, and the rate came to only 2 per year on average until 2000. In this century, things have been relatively better, but only relatively, and the publication of Lilavati’s Daughters (indicated by the arrow) may or may not have played much of a role in the process. Nevertheless, the slow but sure increase in the numbers – the overall positive derivative, in other words – is undeniable and very welcome.

When they started in 2005, the WiS panel has had a difficult course to chart. Then – and for that matter, even now – the number of women Fellows of the Academy was below 10% of the total Fellowship. Although women had been in the Academy right from the beginning – E.K. Janaki Ammal was a Foundation Fellow of the Academy, elected in 1935 (in contrast, the Royal Society formed in London in 1660 first admitted women in 1945, and the French Academy of Sciences, founded in 1666 would wait till 1979 to have its first female member). But the numbers only grew very very slowly: the (smoothed) graph on the right shows just how slow the change was. The second woman Fellow was elected in 1960, the third in 1962, and the rate came to only 2 per year on average until 2000. In this century, things have been relatively better, but only relatively, and the publication of Lilavati’s Daughters (indicated by the arrow) may or may not have played much of a role in the process. Nevertheless, the slow but sure increase in the numbers – the overall positive derivative, in other words – is undeniable and very welcome.

Another indication that the times are a changing is the relative ease with which gender issues can be discussed openly. Issues such as gender bias, as well as harassment are often out in the open, with organizations such as BiasWatch India being quite active. Institutions have programs to address implicit as well as explicit bias, and in addition to Women in Science panels in different Academies, there are groups that bring together women working in different areas, one example being the Gender in Physics Working Group. At the same time, there are hurdles that women still face, especially when it comes to integrating all the different parts of one’s life – managing a research group along with one’s personal challenges, whatever those might be. One of the contributors to LD put it so: “The complexities of negotiating gender and professional roles tend to become most acute for most women in their late twenties and thirties. This is partly because these are the years when decisions regarding marriage and children are made but also because these are the years when one has to establish one’s academic independence and viability.”

In recent years there have been new and different approaches to telling the story of women in science in India, and as the number of science communicators in the country grows, these are also more about the science. A number of recent books share a similar format with Lilavati’s Daughters, being collections of short essays on a diverse group of scientifically successful women. These are easy to dip into, and are all truly inspiring, pointing to the fact that there are many stories to tell and there is a need to tell these stories again and again. I list some below – these are all available quite easily at online bookstores:

- Women Scientists in India: Lives, Struggles and Achievements by Anjana Chattopadhyay (2018)

- She Can You Can by Garima Kushwaha (2019)

- 31 Fantastic Adventures in Science: Women Scientists in India by Nandita Jayaraj and Aashima Freidog (2019)

- Women in Science and Technology by Namrata Gupta (2019)

- ISRO Magnificent Women and their Flying Machines by Minnie Vaid(2020)

- Lady Doctors: The Untold Stories of India’s First Women in Medicine by Kavitha Rao (2021)

- Gutsy Girls Of Science by Ilina Singh (2022)

- The Pioneer Indian Meteorologist: True life Story of The First Indian Female Scientist Know as the “Weather Woman of India” by Sarah K. Folden (2022)

- Lab Hopping: Women Scientists in India by Nandita Jayaraj and Aashima Freidog (2023)

- Indian Women Scientists: Unsung Stories by Dr. Vijaya Sinha (2023)

- Girl Power: Indian Women who Broke the Rules by Neha J Hiranandani (2023)

- Indian Women In Science by Kaveri Shrihari (2023)

There is also the superbly detailed 2022 biography, Chromosome Woman, Nomad Scientist: E. K. Janaki Ammal, A Life 1897–1984 by Savithri Preetha Nair that brings out the life and work of Janaki Ammal. To quote from the blurb, “The volume brings into focus her work on mapping the origin and evolution of cultivated plants across space and time, to contribute to a grand history of human evolution, her works published in peer-reviewed Indian and international journals of science, as well as her co-authored work, Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants (1945), considered a bible by practitioners of the discipline.” There are many more such important stories that need to be written.

There is also the superbly detailed 2022 biography, Chromosome Woman, Nomad Scientist: E. K. Janaki Ammal, A Life 1897–1984 by Savithri Preetha Nair that brings out the life and work of Janaki Ammal. To quote from the blurb, “The volume brings into focus her work on mapping the origin and evolution of cultivated plants across space and time, to contribute to a grand history of human evolution, her works published in peer-reviewed Indian and international journals of science, as well as her co-authored work, Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants (1945), considered a bible by practitioners of the discipline.” There are many more such important stories that need to be written.

We closed our preface to LD by expressing thanks to our contributors for helping to make it a very personal book that conveyed the courage, dedication, and aspiration of Indian women in science, touching the hearts and minds of the reader. But in the end the value of LD will be gauged by the real difference that comes about in the scientific workplace, the day when gender considerations will cease to play a determining or limiting role.

It is too early to tell, but the optimist in us feels that the signs are encouraging!

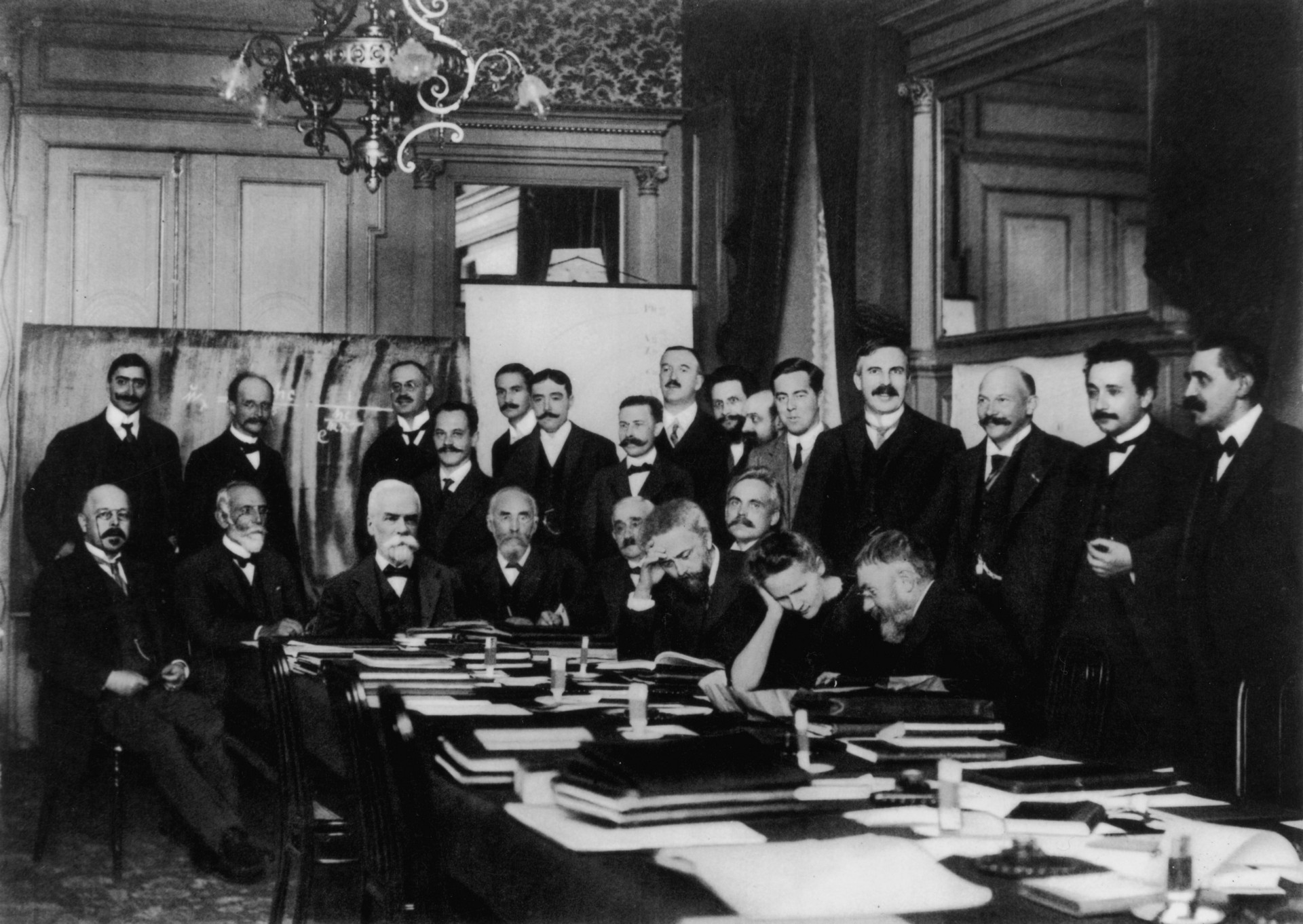

When the first

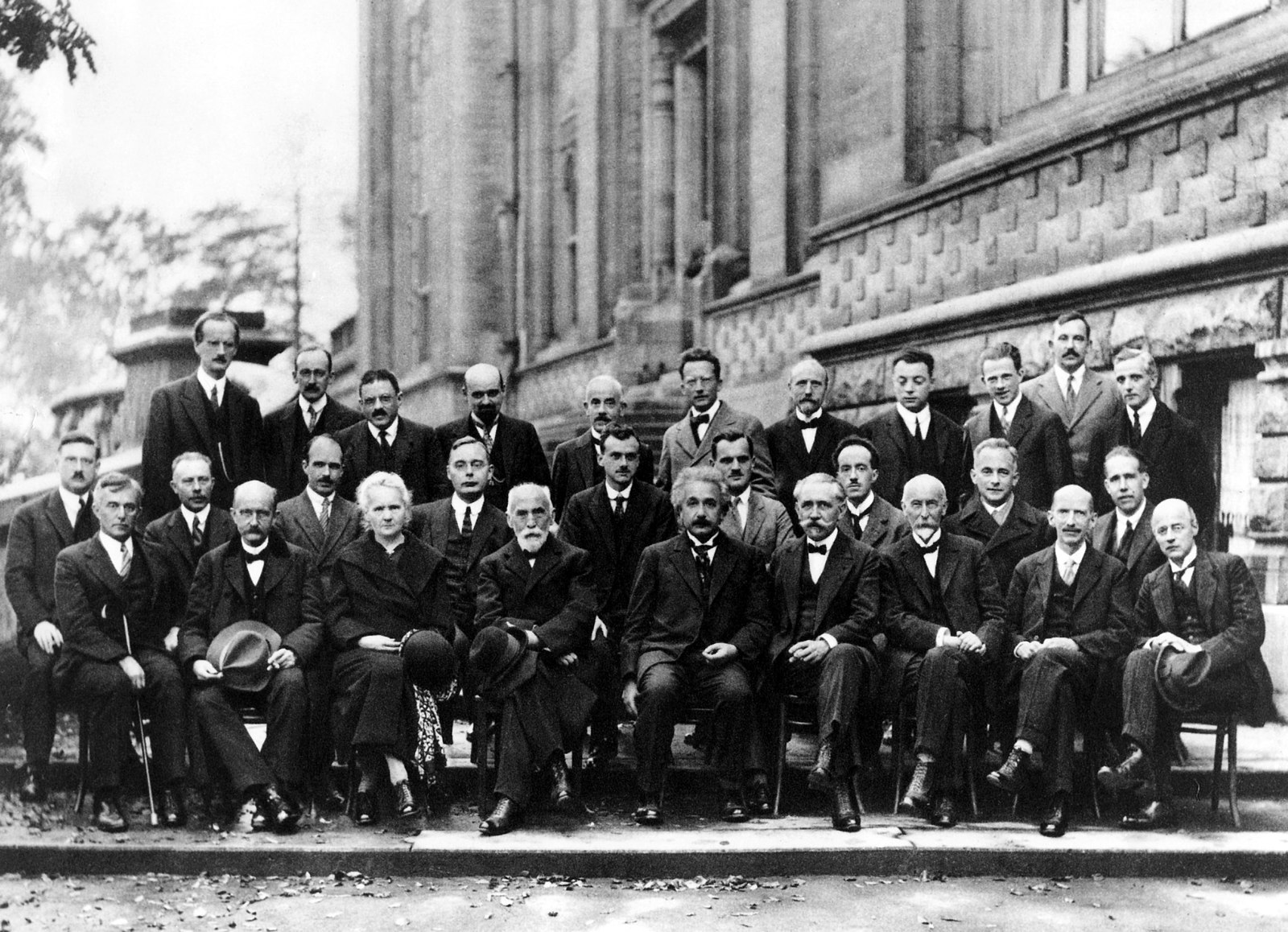

When the first  Sixteen years later, when the fifth Solvay was held in 1927, she still was the only woman at the meeting although by then she had her second Nobel prize (in chemistry, in 1911). There were some other women who might have been invited to the meeting on quantum physics – Lise Meitner had been appointed Professor of Physics in Berlin in 1926 (she would go on to discover nuclear fission) and the mathematician Emmy Noether who made seminal contributions in mathematical physics. There may have been others as well, but the bar had been set high: the next woman to be awarded the Nobel prize in physics was Maria Goeppert-Mayer, in 1963…

Sixteen years later, when the fifth Solvay was held in 1927, she still was the only woman at the meeting although by then she had her second Nobel prize (in chemistry, in 1911). There were some other women who might have been invited to the meeting on quantum physics – Lise Meitner had been appointed Professor of Physics in Berlin in 1926 (she would go on to discover nuclear fission) and the mathematician Emmy Noether who made seminal contributions in mathematical physics. There may have been others as well, but the bar had been set high: the next woman to be awarded the Nobel prize in physics was Maria Goeppert-Mayer, in 1963… But this post is mainly about a Conference and some Workshops that will be held in the coming week that relate to this issue. The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (or IUPAP) which in some sense represents physicists worldwide decided to create a Women in Physics (WiP) Working Group (WG5) in 1999 with the main aim being to suggest means to “improve the situation for women in physics. Since this is a global organization, the hope was to use the strength of numbers to address an issue that did not seem to change over the years

But this post is mainly about a Conference and some Workshops that will be held in the coming week that relate to this issue. The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (or IUPAP) which in some sense represents physicists worldwide decided to create a Women in Physics (WiP) Working Group (WG5) in 1999 with the main aim being to suggest means to “improve the situation for women in physics. Since this is a global organization, the hope was to use the strength of numbers to address an issue that did not seem to change over the years WG5 has taken more onto its plate and now this group is also given the task of suggesting means to increase gender diversity and inclusion in the practice of physics and to promote and take actions to increase gender diversity and inclusion across countries and regions. One of the outcomes of the general global awareness was the creation of the

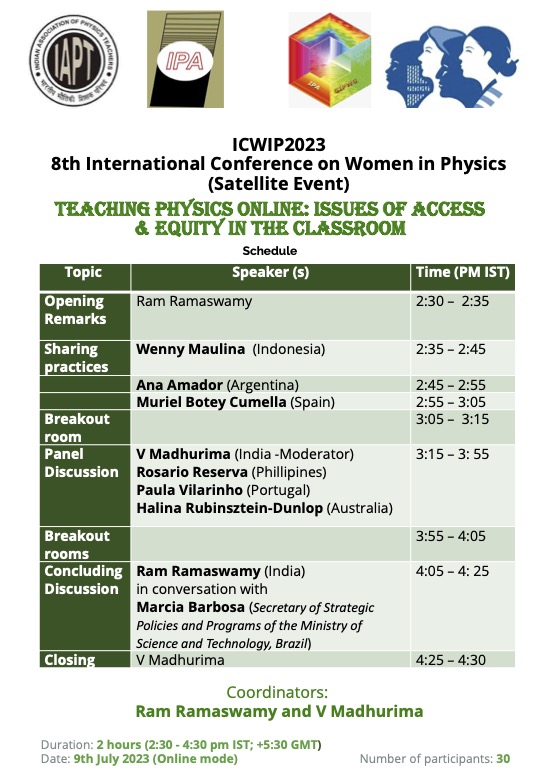

WG5 has taken more onto its plate and now this group is also given the task of suggesting means to increase gender diversity and inclusion in the practice of physics and to promote and take actions to increase gender diversity and inclusion across countries and regions. One of the outcomes of the general global awareness was the creation of the  Teaching Physics Online: Issues of Access & Equity in the Classroom

Teaching Physics Online: Issues of Access & Equity in the Classroom  I’ve written about DFOT on this

I’ve written about DFOT on this