Last year Sujin Babu — earlier a student at the University of Hyderabad and now a teacher at Mount Carmel College in Bangalore — wrote to ask my take on online education in India. This was shortly after the pandemic had caused the first lockdown and I had no real sense of how things were evolving, so I gave some waffly answer… But as classes returned online, it was clear to both of us that the question would be of wider interest, given how the times they were a-changin’.

We asked a group of teachers and students as to how they were reacting to the shift to online teaching. Different subjects, different kinds of institutions, different geographical locations… Some attempt to capture the diversity of the academic landscape in India. The resulting twenty essays were published online in Confluence, the online discussion forum of the Indian Academy of Sciences between July and November 2020.

We asked a group of teachers and students as to how they were reacting to the shift to online teaching. Different subjects, different kinds of institutions, different geographical locations… Some attempt to capture the diversity of the academic landscape in India. The resulting twenty essays were published online in Confluence, the online discussion forum of the Indian Academy of Sciences between July and November 2020.

In our initial call for articles, we had noted that “this pandemic has, as we increasingly realize, the potential to change the entire world order. In some quarters this is already seen as a historical divide, BC (before Corona) and AC (after Corona). Across the globe educational systems at all levels have been seriously impacted even in this short span of time. The virus SARS-CoV-2 (and the diseases it causes, COVID-19) has affected all schools, colleges and universities. By mid-March mostly, these have all been shut: classes have been suspended, examinations, research work and virtually all laboratory experiments have been forced to hit the “pause button”. Students everywhere are in limbo, facing an uncertain present, and a more uncertain future.”

We also felt that some of the changes were going to be long-term and that we – as a community of teachers and students – had not been given any time to adapt. In our initial call for articles, we realized it was early to ask for reactions, but also that “now is as good a time as any to start thinking about these matters. Online classes have been thrust upon all sorts of institutions largely because there seem to be few options, but the experience so far has been very mixed. This discussion is therefore intended to gather the experiences and thoughts about the present and future of the education with regard to the pandemic, from academicians and non-academics cutting across disciplines and geographical boundaries.”

The collection of articles is now available as an eBook, free to download from the website of the Indian Academy of Science. In the Preface to the collection of articles (excerpted below) we talk about the challenges and opportunities we see emerging.

Which brings us to today

It is now almost a year since the pandemic was declared, a year of living precariously… Across the world, education has been drastically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Most instruction has moved online. Schools, colleges, universities and research establishments have been shut for this semester and with no idea of when it will be possible to safely reopen, the lockdown of education may well extend beyond 2020. Where possible, higher education has gone digital, and where not possible, as in practicals for example, it has simply been put on hold.

In the wake of the pandemic, other countries have embraced online education with mixed enthusiasm. Universities in the United Kingdom, the United States have also announced that the coming academic year will be held mainly online. At the same time, educationists and policy makers advise caution: Online education has not lived up to its potential. At least not yet.

Given our diversity in institutions of higher education — private and governmental colleges and universities, research institutes, professional colleges, State and central universities and so on — the Indian education system has had a very heterogeneous response to the pandemic. The reactions also reflect the contrast in rural versus urban infrastructure, the variable quality of staff, and the diverse types of subjects that are taught. There will be serious long-term effects considering the scale of the social, political and economic changes that have been occurring these past several months.

The NEP 2020

An unanticipated entrant into the various equations that are being worked out now is the recently introduced National Education Policy 2020 that was introduced in Parliament in July 2020 and adopted by the Government. Although written well before the pandemic, the NEP-2020 has much to say about online education in Section 24, a short summary of which is given below.

The National Education Policy 2020 calls for carefully designed and appropriately scaled pilot studies to determine how the benefits of online/digital education can be reaped. The existing digital platforms and ongoing ICT-based educational initiatives must be optimized and expanded to meet the current and future challenges in providing quality education for all. The digital divide needs to be eliminated through concerted efforts. It is important that the use of technology for online and digital education adequately addresses concerns of equity. Teachers require suitable training and development to be effective online educators. Aside from changes required in pedagogy, online assessments also require a different approach. Online education also needs to be blended with experiential and activity-based learning. The Policy recommends:

- Pilot studies for online education: Agencies, such as the NETF, CIET, NIOS, IGNOU, IITs, NITs, etc. will be identified to conduct a series of pilot studies, in parallel, to evaluate the benefits of integrating education with online education

- Augmenting Digital infrastructure: There is a need to invest in creation of open, interoperable, evolvable, public digital infrastructure in the education sector that can be used by multiple platforms and point solutions, to solve for India’s scale, diversity, complexity and device penetration.

- Online teaching platforms and tools: Appropriate existing e-learning platforms such as SWAYAM, DIKSHA, will be extended to provide teachers with a structured, user-friendly, rich set of assistive tools for monitoring progress of learners

- Content: A digital repository of content including creation of coursework will be developed, with a clear public system for ratings by users on effectiveness and quality.

- Addressing the digital divide: Given the fact that there still persists a substantial section of the population whose digital access is highly limited, the existing mass media, such as television, radio, and community radio will be extensively used for telecast and broadcasts.

- Virtual Labs: Existing e-learning platforms will be leveraged for creating virtual labs so that all students have equal access to quality practical and hands-on experiment-based learning experiences.

- Pedagogy and Evaluation: Teachers will undergo rigorous training in learner-centric pedagogy. Appropriate bodies, such as the proposed National Assessment Centre or PARAKH, School Boards, NTA, and other identified bodies will design and implement assessment frameworks

- Blended models of learning: Different effective models of blended learning will be identified for appropriate replication for different subjects.

These various initiatives and more need to be undertaken as soon as possible. The NEP 2020 imagined that online education will be limited to certain spheres instead of having the substantially wider applicability that is apparent in the wake of the pandemic. The digital divide needs to be addressed now, infrastructure needs to be augmented now, and the efforts in pedagogy revision and teacher training is a current necessity.

When we started this exercise in April 2020, our aim was to be educated by our colleagues about the issues that they faced as a consequence of the abrupt move from the classroom to the internet. What is slowly becoming clear is that the effects of this pandemic will last a substantially longer time than had been anticipated, and moreover, the social, economic, and political effects of the pandemic will also be substantial and in ways that cannot be predicted just yet. Our call was for teachers and students across India to share their experiences of education during the crisis and to discuss their personal view of the future, keeping their institutions and subjects in mind.

From a purely pedagogical point of view, it is clear that technology will play a bigger role in education in the coming years. However, it will be highly subject-specific. Courses that traditionally need a laboratory or practical component are an obvious example where online classes cannot offer an alternative. The adoption or integration of technology in education depends on the specific institution and its location: there is a huge digital divide in the country in terms of bandwidth and reliable connectivity, as well as very unequal access to funding.

Beyond classroom lectures and courses, there has been a serious impact on academic research in all disciplines. There is a need for close personal interaction and discussion in research supervision, and it is not clear when and how doctoral research and supervision can resume. Research involves interaction between neophytes and their mentors. In research, the role of tacit knowledge is extremely important which can only be gained by the young researchers in constant interaction with their mentors. How can digital education be designed so that there is transmission of tacit knowledge? In addition, the related economic crisis has consequences for funding, both of research as well as for the maintenance of research infrastructure. These are very long-term effects.

The hard truth

Some matters are are all too self-evident. Access to the Internet is very unequal, and more than half the students in any class in any institution are simply not able to attend lectures in real time for want of the required combination of hardware, electrical connectivity, and study space within their homes. Erratic network connection has also been a major hurdle for the students. This is more pronounced in rural areas and non-metro cities, and for lower income groups.

Most teachers in India view online instruction with trepidation. The shift online is in response to a crisis and was poorly planned. Online teaching is a separate didactic genre in itself — one that requires investment of time and resources that very few teachers could come up with in a hurry. Many online classes are poorly executed video versions of regular classroom lectures. Across the board, teachers recognise this as unsatisfactory,

Keeping the NEP 2020’s recommendation in mind, there is an urgent need for training, both in-house and across the board. Many smaller institutions cannot afford the costs of retraining their faculty and also in investing in the required infrastructure for online teaching. It is a fact that the majority of teachers deliver their classes from their homes, where full facilities may not be available. In addition, many teachers have invested a large part of their careers in classroom teaching, something that cannot easily be unlearned in the online context. There is pressure on teachers to become digital experts, when the truth is that most teachers are not equipped enough to incorporate technology into education and are hesitant to do so. Overcoming this lack of proficiency in technology has to be a priority for both teachers and students.

Online higher education using MOOCs, or massive open online courses, has been encouraged by the Ministry of Human Resource Development for some time now via the National Programme on Technology Enhanced Learning (NPTEL) and SWAYAM platforms. (SWAYAM is an acronym for “Study Webs of Active-Learning for Young Aspiring Minds”.) If this is to make a serious difference, both the quality and quantity of online courses need to be enhanced. These are presently used to augment classroom instruction but if these can be taken for credit, it may help address the question of access to quality education. There is a positive aspect of even a partial move to online education: making lectures available online in public and open websites accelerates democratisation of knowledge and the wide distribution of learning opportunities.

At present the campuses of universities and colleges in our country provide democratic space for students and teachers to express their ideas without fear and students can, regardless of gender, caste, tribe, economic or social class, all interact as equals. Universities in this sense contribute to democratic culture. Assuming that the significance of campuses decline overtime with the shift to online education, how will we create opportunities for enhancing this democratic culture? Can we think of digital democracy? What are the contours of digital democracy in a country like ours? In the online mode, opportunities for students to interact as members of a cohort pursuing a degree programme may decline with the decline of campus-based education that we have become used to. This change will have several social and psychological implications.

It is widely appreciated that education is not simply about the learning in the classroom alone, it is also about the various activities that happen outside the four walls of the classroom. Extracurricular activities such as literary and debate events, quizzes, cultural festivals, theatre, sporting events, activities of NSS, scrub societies, academic paper presentations etc. are a few that are difficult to replicate on online platforms since most of them demand the physical gathering of students. Another of the less obvious casualties of the online space is good teacher-student relationships. Many teachers feel that this is essential, and is only possible to develop in the physical classroom. Teachers may not be able to assess the strength and weakness of the students in a virtual classroom whereas in a physical classroom, the teacher can cater the needs of every student because of closeness they share. We clearly need to find suitable alternates for this form of interaction.

Examinations and continuous assessment are part of the education process, and this cannot be simply set aside for now. Students will care less for examinations if they are conducted online, since they know that they would pass them by any means. A lack of seriousness towards evaluation will affect quality of the certification. It is impossible to implement e-surveillance through online teaching applications, when the applications are already being accused of privacy breach. Some tools are available, but their reliability needs to be verified.

An opportunity for change

This is also a chance to re-imagine higher education in India. For long, this has been elitist and exclusionary; education has been less about learning and more about acquiring degrees. The pandemic can change that, if we let it.

Our higher education system can be more inclusive. If going online loses the human touch, the advantage of becoming available to more people who aspire to learn is worth the trade-off. If giving proctored examinations in a socially distanced world is more difficult, what needs to change is the idea of proctored examinations. There are simpler ways to validate pedagogy, some of which can be found in our own traditions. Gandhiji’s “Nai Talim” put a high premium on self-study and experiential learning, for instance.

Some part of the traditional curriculum and examinations can also be replaced by experiential learning that existed in the ancient India. Experiential learning can give more autonomy to both the teacher and the student: a teacher directing the way, while the student chooses the desired path. Examinations can also be restructured by giving more autonomy to teacher to form the syllabi according to the tastes of the students.

Significant qualitative changes can come about if we plan now. Digital tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) — already used in teaching language — can be adapted to deliver personalised instruction based on learning needs for each student. The use of AI can improve learning outcomes; in particular, this can be a boon for teaching students who are differently abled.

The adoption of online education needs to be done with sensitivity. What is needed now is imagination and a commitment to decentralisation in education. Pedagogic material must be made available in our other national languages; this will expand access, and can help overcome staff shortages that plague remote institutions. The State will have to bear much of the responsibility, both to improve digital infrastructure and to ensure that every needy student has access to a laptop or smartphone. Technological infrastructure for the preparation of the content and dissemination of the content has to be put in place.

Universities have to reform their academic administration, the way of conducting examinations and organizing digital classes – interactive online classes. Teachers have to change their style of teaching and learn to interact with students in virtual space in contrast to the current interaction in physical space. Teachers have to be trained on the new methods of pedagogy. Students have to change their attitude to learning. Online learning demands more involvement and effort, for example, a lot of self-study. Students should have a choice to pursue courses. The choice-based credit system (CBCS) has to be reconfigured.

Campuses across India are desolate now, empty and inactive. Estimates are that COVID-19 will be seasonal, recurring every so often till 2022 or maybe 2024. When these institutions reopen, they must do so with extreme caution. Blended modes of education will be unavoidable: online instruction where possible, and limited contact for laboratory instruction and individual mentoring.

The phoenix is a good metaphor for a possible resurgence, as our universities (hopefully) learn to reinvent themselves. But some of the old must go, as it makes way for the new… There is an urgent need for this, for our leadership – local as well as national – to see that some of the older models and even older degrees may not really mean very much any more and should yield to a new pedagogic paradigm. What this new paradigm should be, precisely, is something that we need to collectively reflect upon: it is important that we should make good use of this opportunity.

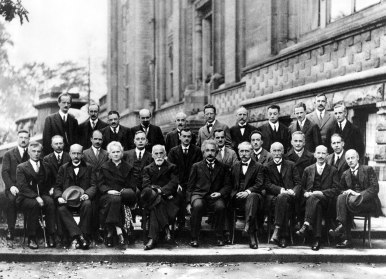

When the first Solvay Conference was organized in 1911 to discuss current problems in Physics and Chemistry, Marie Curie was the only woman invited. It probably took her 1903 Nobel prize in physics to secure her place at the table, though in all fairness, many (but not all) of the men there were Nobel laureates.

When the first Solvay Conference was organized in 1911 to discuss current problems in Physics and Chemistry, Marie Curie was the only woman invited. It probably took her 1903 Nobel prize in physics to secure her place at the table, though in all fairness, many (but not all) of the men there were Nobel laureates. Sixteen years later, when the fifth Solvay was held in 1927, she still was the only woman at the meeting although by then she had her second Nobel prize (in chemistry, in 1911). There were some other women who might have been invited to the meeting on quantum physics – Lise Meitner had been appointed Professor of Physics in Berlin in 1926 (she would go on to discover nuclear fission) and the mathematician Emmy Noether who made seminal contributions in mathematical physics. There may have been others as well, but the bar had been set high: the next woman to be awarded the Nobel prize in physics was Maria Goeppert-Mayer, in 1963…

Sixteen years later, when the fifth Solvay was held in 1927, she still was the only woman at the meeting although by then she had her second Nobel prize (in chemistry, in 1911). There were some other women who might have been invited to the meeting on quantum physics – Lise Meitner had been appointed Professor of Physics in Berlin in 1926 (she would go on to discover nuclear fission) and the mathematician Emmy Noether who made seminal contributions in mathematical physics. There may have been others as well, but the bar had been set high: the next woman to be awarded the Nobel prize in physics was Maria Goeppert-Mayer, in 1963… But this post is mainly about a Conference and some Workshops that will be held in the coming week that relate to this issue. The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (or IUPAP) which in some sense represents physicists worldwide decided to create a Women in Physics (WiP) Working Group (WG5) in 1999 with the main aim being to suggest means to “improve the situation for women in physics. Since this is a global organization, the hope was to use the strength of numbers to address an issue that did not seem to change over the years

But this post is mainly about a Conference and some Workshops that will be held in the coming week that relate to this issue. The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (or IUPAP) which in some sense represents physicists worldwide decided to create a Women in Physics (WiP) Working Group (WG5) in 1999 with the main aim being to suggest means to “improve the situation for women in physics. Since this is a global organization, the hope was to use the strength of numbers to address an issue that did not seem to change over the years WG5 has taken more onto its plate and now this group is also given the task of suggesting means to increase gender diversity and inclusion in the practice of physics and to promote and take actions to increase gender diversity and inclusion across countries and regions. One of the outcomes of the general global awareness was the creation of the Gender in Physics Working Group (GIPWG) of Indian Physics Association (IPA), the main moving force behind the push to bring this conference to India.

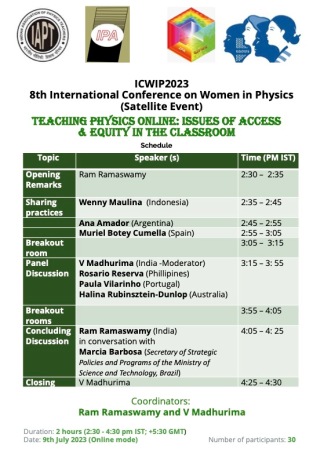

WG5 has taken more onto its plate and now this group is also given the task of suggesting means to increase gender diversity and inclusion in the practice of physics and to promote and take actions to increase gender diversity and inclusion across countries and regions. One of the outcomes of the general global awareness was the creation of the Gender in Physics Working Group (GIPWG) of Indian Physics Association (IPA), the main moving force behind the push to bring this conference to India. Teaching Physics Online: Issues of Access & Equity in the Classroom will be an online meeting from 2:30-4:30 pm IST on Sunday, 9th July. Since the theme for the International Women’s Day 2023 was specified by the UN to be DigitAll – Innovation and technology for gender equality, this seemed like a good discussion point, especially since already before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe, education was leaning towards online modes through the use of MOOCs. Post-pandemic, online education is here to stay. In India, this is reflected in the National Education Policy 2020 which has a large online education component. On the one hand there is a noticeable gender inequity in access to digital devices and internet, and on the other hand, the amount of time available to women teachers (and students) is restricted by societal norms.

Teaching Physics Online: Issues of Access & Equity in the Classroom will be an online meeting from 2:30-4:30 pm IST on Sunday, 9th July. Since the theme for the International Women’s Day 2023 was specified by the UN to be DigitAll – Innovation and technology for gender equality, this seemed like a good discussion point, especially since already before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the globe, education was leaning towards online modes through the use of MOOCs. Post-pandemic, online education is here to stay. In India, this is reflected in the National Education Policy 2020 which has a large online education component. On the one hand there is a noticeable gender inequity in access to digital devices and internet, and on the other hand, the amount of time available to women teachers (and students) is restricted by societal norms. I’ve written about DFOT on this blog before, but one thing we thought was whether we could use the occasion of ICWIP to have a discussion with physics teachers in India on just how effective the online medium can be when there is no pandemic to worry about, and what the gender dimension is in practice. On the 8th of July, we will have a Workshop on Teaching Physics Effectively Online an in-person meeting at GITAM. Teachers who are participating in the discussion include Bindu Bambah, Rukmani Mohanta, Barilong Mawlong (all from the University of Hyderabad), Venkatesh Chopella (IIIT) Meenakshi Viswanathan (BITS-Pilani) and Sai Preeti (GITAM). There will also be a hybrid lecture by Vandana Sharma of the IIT Hyderabad on Imaging assisting Humankind: Fundamental Science to Application and hopefully there will be a link to the online talk here.

I’ve written about DFOT on this blog before, but one thing we thought was whether we could use the occasion of ICWIP to have a discussion with physics teachers in India on just how effective the online medium can be when there is no pandemic to worry about, and what the gender dimension is in practice. On the 8th of July, we will have a Workshop on Teaching Physics Effectively Online an in-person meeting at GITAM. Teachers who are participating in the discussion include Bindu Bambah, Rukmani Mohanta, Barilong Mawlong (all from the University of Hyderabad), Venkatesh Chopella (IIIT) Meenakshi Viswanathan (BITS-Pilani) and Sai Preeti (GITAM). There will also be a hybrid lecture by Vandana Sharma of the IIT Hyderabad on Imaging assisting Humankind: Fundamental Science to Application and hopefully there will be a link to the online talk here.

The earlier call resulted in some twenty articles that covered different aspects of the pandemic-induced move to online education. These have been collected as an e-book,

The earlier call resulted in some twenty articles that covered different aspects of the pandemic-induced move to online education. These have been collected as an e-book,  The introduction of the National Education Policy 2020 in the middle of the pandemic year, with little debate and even less analysis has been a major challenge. Not only did one have to cope with a changed medium of instruction, one also had to incorporate structural changes that were imposed from the top, as opposed to those that might have developed organically. The future of higher education in India, given the scale of the social, political and economic changes that have occurred in the past several months, is therefore quite uncertain.

The introduction of the National Education Policy 2020 in the middle of the pandemic year, with little debate and even less analysis has been a major challenge. Not only did one have to cope with a changed medium of instruction, one also had to incorporate structural changes that were imposed from the top, as opposed to those that might have developed organically. The future of higher education in India, given the scale of the social, political and economic changes that have occurred in the past several months, is therefore quite uncertain.

We asked a group of teachers and students as to how they were reacting to the shift to online teaching. Different subjects, different kinds of institutions, different geographical locations… Some attempt to capture the diversity of the academic landscape in India. The resulting twenty essays were published online in

We asked a group of teachers and students as to how they were reacting to the shift to online teaching. Different subjects, different kinds of institutions, different geographical locations… Some attempt to capture the diversity of the academic landscape in India. The resulting twenty essays were published online in